There was a section in Apple’s big June event that, while strenuously earnest, doubled as a pretty good joke. After dozens of product announcements, including new computers, operating systems, and software updates, Apple highlighted a pair of features focused on its users’ well-being.

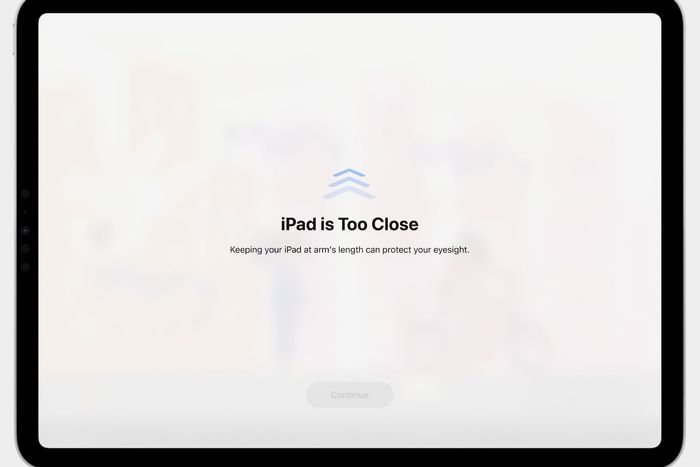

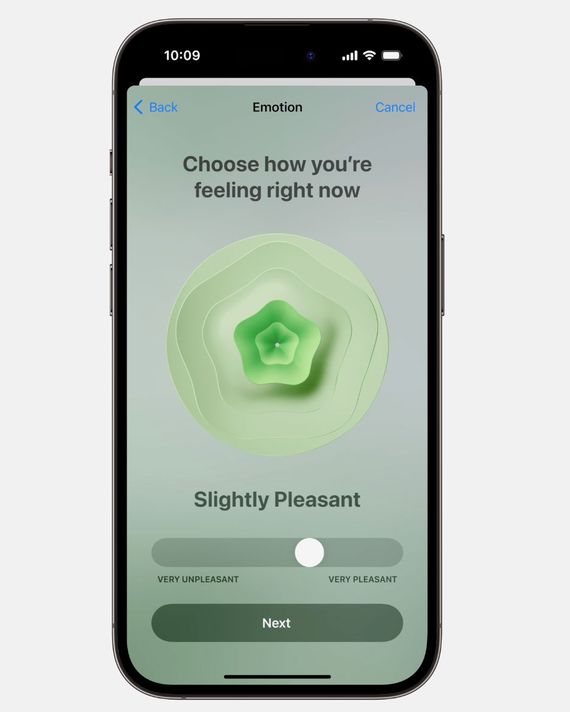

One was a new Mindfulness app in which users can log their “momentary emotion” and “daily mood,” compiling a diary of feelings and their causes — perhaps family time makes you happy and time working in front of screens makes you sad — which could be reflected back as insights that might help make things better. The other was a set of tools for improving users’ “vision health,” with a focus on myopia, which, according to Apple, is expected to affect half the population by 2050, up from 30 percent today. Using data from device sensors, Apple will instruct users — especially but not exclusively young ones — to go outside, into the natural light, or to move their screens further from their faces, a sort of data-driven version of the parental warning not to sit so close to the TV or else you’ll go blind.

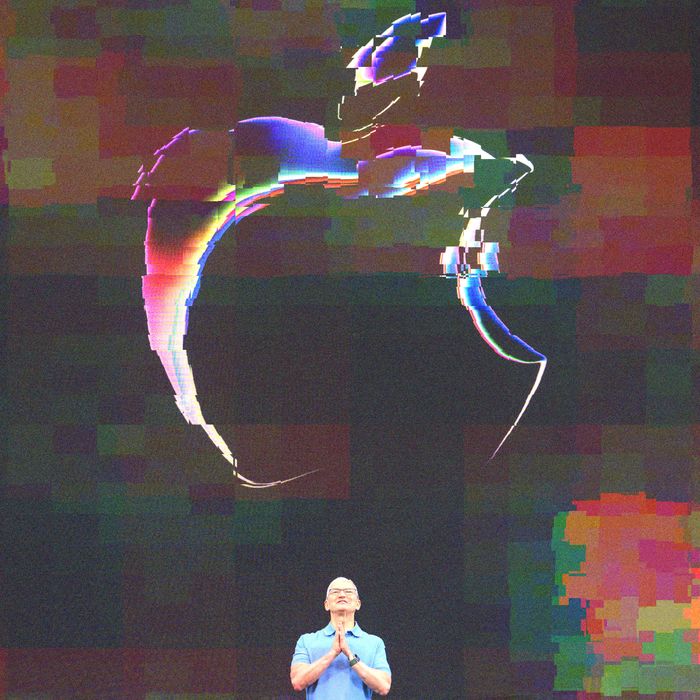

That was the setup: Apple is helping users help themselves, giving them tips and tricks and tools for managing modern life. Then, after a beat, Tim Cook returned to the stage to deliver the punchline in the form of an all-new product: the Vision Pro, a $3,500 computer that straps directly to your face.

The Apple Vision Pro is a camera-and-sensor-laden headset that mediates the entire world through screens placed centimeters from users’ corneas, which are themselves projected onto an exterior screen to assure others you aren’t entirely lost to the world. By present standards, which could of course be rendered naïve in hindsight, it’s the most dystopian product Apple has ever announced — the sort of thing that, if were I recording my emotional state on my iPhone, I might log as “slightly unpleasant” to contemplate but also “slightly exciting” to try. Apple knows the modern world is getting you down, and is in fact literally destroying your eyes, and understands that it might bear some responsibility for the whole situation, so it would love to help and has some ideas. But first, and forever: one more thing.

Like any good joke, Apple’s mixed messaging about mixed reality contained an element of uncomfortable truth. In succeeding as a seller of premium electronics, Apple has, over the past few decades, become one of the most powerful companies in the world and not entirely in ways its leaders intended or predicted. The sheer amount of time that Apple’s customers spend with its products — phones that never leave their sides, computers on their desks, watches and TV boxes and earbuds and home assistants — makes their full influence hard to account for. Whatever your customer is going through, and however life is going, Apple’s products are present and frequently involved. It’s nice our devices have features to make us feel and act and be better, but, considering the source, its advice can sound a bit rich. Oh, it’s time to rest my eyes and collect my thoughts? Is that so, phone?

The Vision Pro makes literal Apple’s current position in millions of users’ lives, as a company that mediates their experience of the world around them, their work, and their relationships with other people. It’s a position from which it might be easy to mistake issues with your product for problems with your customers. From there, it might be tempting to address those problems with your customers in the inexorable product cycle — as you might fix bugs or upgrade obsolete technologies.

Apple isn’t identified with the most overtly predatory and alienating aspects of the 21st-century digital life — the data-driven advertising and social-media companies, which explicitly grind the stuff of humanity into monetizable units – but it is, at minimum, their vital accomplice. Steve Jobs famously talked about nascent personal computers as “bicycles for the mind.” Now, for many of its users, the iPhone is a machine for looking at Instagram and watching TikTok. It has become a de facto anti-empowerment device, a conduit for passive consumption, an interface through which identities and waking hours are continuously strip-mined by companies like Meta and Google and TikTok, a device with which users know they should probably spend a bit less time for their own good.

Apple’s products are thoughtfully designed with evidence of careful consideration in the smallest details, but a commitment to good design can only do so much if the product is a portal to the same greasy, exploitative, exhausting, stimulating digital economy in which the customer otherwise lives and works. (Neither are smartphones the only type of product to present such a dilemma. Automakers keep making nicer cars with increasingly assertive interventions into driver behavior resulting in relative improvements in safety; meanwhile, for reasons beyond the control of any single automaker, drivers spend huge amounts of time sitting in their cars instead of doing something more productive or fulfilling to the clear detriment of their health, the health of their communities, and the safety of other people.)

This has presented a vexing marketing problem for Apple, a company that has, historically, been pretty good at telling its own story. It’s no longer the underdog it was in the ’90s, the smugly superior PC alternative poking fun at its stodgy rivals in the aughts, or just a company that makes nice gadgets, like the iPod, that you and millions of other people might want to buy. The absolute success of the iPhone, now 16 years old, turned Apple into a symbol of queasy modernity — less a company that customers choose to patronize than an institution they’re a bit stuck with.

Apple, with its widely watched and covered product events, charts the future of human-machine interaction on a yearly schedule of not-so-secret and mostly unsurprising updates, its upbeat, upscale keynotes increasingly divorced from the complicated, conflicted experiences of the average smartphone user. The phones that show up in the presentations are, of course, notably and unrealistically devoid of the trash that often dominates its customers’ screens and time. We see Apple employees and theoretical customers scheduling ski trips, powerfully manipulating gorgeous photos, and connecting tenderly and deliberately with other people. We don’t see them dismissing hundreds of notifications throughout their days, or answering work emails before bed, or drawing their phones from their pockets after the briefest lull in a real-life conversation, unsure what they’re looking for but unable to suppress the reflex.

When Apple does acknowledge this gap, it positions itself as part of the solution, as an ally in the quest for a better you, or at least a better user, and against less conscientious actors in tech. In doing so, Apple has adopted a familiar playbook. The $3 trillion corporation wants its customers to behave differently without alienating them or becoming too implicated in the problems they want to solve — so it’s become a nudger.

The nudge is a behavioral economics concept most associated with the legal scholar for former presidential adviser Cass Sunstein. “A nudge is an intervention that maintains freedom of choice but steers people in a particular direction,” Sunstein has said. “A tax isn’t a nudge. A subsidy isn’t a nudge. A mandate isn’t a nudge. And a ban isn’t a nudge. A warning is a nudge.” (The concept gained political traction during the Obama presidency; the former president established a Social and Behavioral Sciences Team, unofficially known as the “nudge unit,” in hopes of devising non-regulatory approaches to health-care enrollment, student-loan delinquency, and, well, saving paper.)

To engage with virtually any modern software, and to be exposed at all to the online economy of 2023, is to be constantly guided by the thumb, induced into consumption, tipped into a sales funnel, and tricked by “dark patterns” or simple promises of more. To open one’s smartphone is to be subjected to an unending string of self-interested nudges in the direction of various companies’ profitability.

Apple nudges its users around, too, but mostly, at least theoretically, for their own good. In recent years, iOS users will have recognized a widening range of nudges from their devices. Screen Time, introduced in 2018, tracks app usage, reflects it back to users in a report, and offers tools for setting limits. Sound notifications warn users that their headphones have been too loud for too long, threatening their hearing health. By default, Apple products adjust the color temperature of screens according to the time of day to reduce eye strain and improve sleep quality; in the background, iPhones track steps, calories, stairs climbed, walking speed, step length, asymmetry, and steadiness. The Apple Watch, which is explicitly marketed as a health tracker, adds a much wider range of data — heart rate, blood oxygen levels, temperature — with which the company nudges willing users toward health, informing them that it’s time to stand up, that they should move more to “close their rings,” and that, given the quality and quantity of their sleep recently, they should probably start winding down for bed. Apple has a lot of ideas, many of them good, and drawn from real data, about what its users should do to improve their lives. Stand up. Get outside. Turn that volume down. Get some rest. Stop putting the screen — this screen — so close to your face.

Apple’s various nudgelord tendencies differ in a number of ways. Most of the health-tracking features are opt-in and focused on conscious self-improvement. They’re for users who want to exercise more, track sleep, or log medications. They’re tools for addressing preexisting problems, and the nudging is expected and appreciated. Others assume a degree of responsibility for conditions of the smartphone era as, for example, a company that profits from selling devices that might contribute to vision or hearing loss or, with Night Shift, as one of the world’s leading emitters of blue light, which, according to Apple’s marketing materials, can “affect your circadian rhythms and make it harder to fall asleep.” Its new mental-health features fall into this muddled category of, basically, preemptive self-regulation. Would I feel better than “slightly pleasant” if I were doing something other than looking at a screen? By logging enough data, presumably my phone can help me find out. These features, which, if we’re going to be spending so much time with our devices anyway, are almost universally good to have, double as critiques of the smartphone era.

Screen Time crashes straight into the core dilemma here. Apple’s posture as an ally is narrowly tenable — it makes most of its money selling hardware, unlike Meta or Google, for example. Because it doesn’t need to maximize users’ time spent or some other exploitative metric, Apple can provide users support in the form of data and insights to reclaim their own time. It’s using tracking – for good! “By understanding how they’re interacting with their iOS devices, people can take control of how much time they spend in a particular app, website, or category of apps,” Apple said in its Screen Time announcement. In practice, the connection between “understanding” how many many minutes you spend watching YouTube and doing anything about it is tenuous at best. Still, Apple is acknowledging a real problem here — one millions of people with smartphones think and talk about all the time. The company is also making clear that it’s the user’s responsibility.

In the context of government, the most powerful critique of the nudge is that, while often useful, it tends to cast diverse problems as the result of “frailties in individual behavior” rather than the “rules and systems” by and in which people live, precluding the possibility of fundamental change. Similarly, Apple, under the auspices of helping users “take control” of their experiences, makes it clear that, ultimately, all this phone stuff is our fault. It’s up to us. The company that designs and profits from our entire digital context has done all it can. There must be a right and healthy way to live in Apple’s world, the existence of which it regards as both necessary and inevitable, and while it can nudge us in the right direction, it can’t save us from ourselves.

Which, actually, fair enough — we’re not talking about an actual liberal institution shifting responsibility for its own failures back to its citizens in lieu of systemic overhaul. Apple is a massive corporation assuming a slightly hypocritical posture in pursuit of profit, trying to have its cake and eat it too, with a narrative about how it’s the “good” company in a sea of “evil” ones. What’s Apple going to do? Declare the smartphone revolution a mistake, shut down its device division, and tell its shareholders to invest in Samsung and Google? When Tim Cook tells an interviewer that, at Apple, “we try to get people tools in order to help them put the phone down,” and that “if you’re looking at the phone more than you’re looking in somebody’s eyes, you’re doing the wrong thing,” it’s less sinister than silly.

The arrival of the Vision Pro, however, escalates such rhetoric from silly to fully absurd. The “screen time” company with fresh interest in myopia prevention is throwing up its hands and saying fuck it, let’s just put the screen on their faces. The company that wants to help you practice healthy habits is also working on the Alienation Helmet, ready for “all-day” use.

Based on recent experience, it’s fair to imagine a life spent socializing, working, and relaxing in an even more immersive digital environment might produce additional unexpected and unwanted side effects and externalities. The Vision Pro’s mixed-reality concept has the potential to make worries about “screen time” sound quaint — it makes the whole world a screen, and simulates smaller screens within its screens. It also launched with multiple preemptive concessions to its conceptual fissures: those external eyes; workspace backgrounds composed of vivid outdoor environments; scanned avatars to stand in for you in video calls.

I expect, with the Vision Pro, that Apple will find nudging more tempting than ever, especially as its customers unpredictably exceed the narrow, safe use cases outlined in its marketing materials, developing messier and more realistic relationships with their new face computers. Picture it: movement data from an Apple Watch transmitted to an Apple headset, triggering a Vision Pro notification to get some steps in. (Developers have already uncovered new warnings in the Vision Pro’s software, including a message that the user is “Moving at Unsafe Speed.”) The company will acknowledge and address the emerging struggles of helmet life as they arise, with improvements to its product as well as suggestions to its users about how to use it responsibly, based on the underlying assumption that there is — has to be — a right way to use such a thing. Whether that’s actually true is a question Apple can never answer.

More Screen Time

- Uncanny AI Videos Are About to Flood the Internet

- The Other Big Problem With AI Search

- How Siri Made Apple Cautious About AI