This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One weekday in the summer of 2021, Christopher Pence entered his home office in Cedar City, Utah, and plugged a USB stick into his computer. He booted up Tails, an operating system designed to optimize privacy, and used it to access the dark web — a marketplace teeming with illicit goods and services like child pornography, weapons, and drugs. Christopher, who was 41 and worked for Microsoft as a systems engineer, wanted to hire a hit man to kill a young couple he had met on only a handful of occasions.

Christopher was an unlikely client in the murder-for-hire trade. He was not violent and had no criminal record. When he wasn’t logging ten-to-12-hour days working, often while listening to one of his favorite Christian rock bands, he was helping his wife, Michelle, raise their 11 biological and five adopted children. The entire family, along with Christopher’s retired parents, lived in a 5,800-square-foot home on the northern edge of the Mojave Desert, surrounded by wind-raked brushland and snow-capped mountains in all directions. They were building greenhouses on the property and had plans to buy cows.

The Pences were committed Evangelical Christians, and on Sundays they would pile into their 15-passenger Ford Transit and drive north to worship at Valley Bible Church. Afterward, they’d invite church members to their home for fellowship. “If you met them and saw the way that their house was run, it was a joyous, happy atmosphere,” says Tom Jeffcott, the senior pastor of the congregation. “There was a lot of love. It was a structured home, a model of learning, of support, of understanding.” The eldest Pence daughters sometimes harmonized while they washed the dishes.

The Pences had arrived in Cedar City in 2020, and before long Christopher and Michelle confided something troubling to their new pastor. They said they were being hounded by Christina and Francisco Cordero, the biological parents of their five adopted children. The two couples had worked out an agreement that allowed the Corderos some contact with their kids — emails, one phone call a month, two in-person visits a year. But recently, in Christopher’s view, the Corderos had been pushing it. They’d even moved across the country to live closer to the children they’d given up. Jeffcott saw the toll the pressure was taking on his new congregants. To help them find a legal remedy, he introduced them to an attorney.

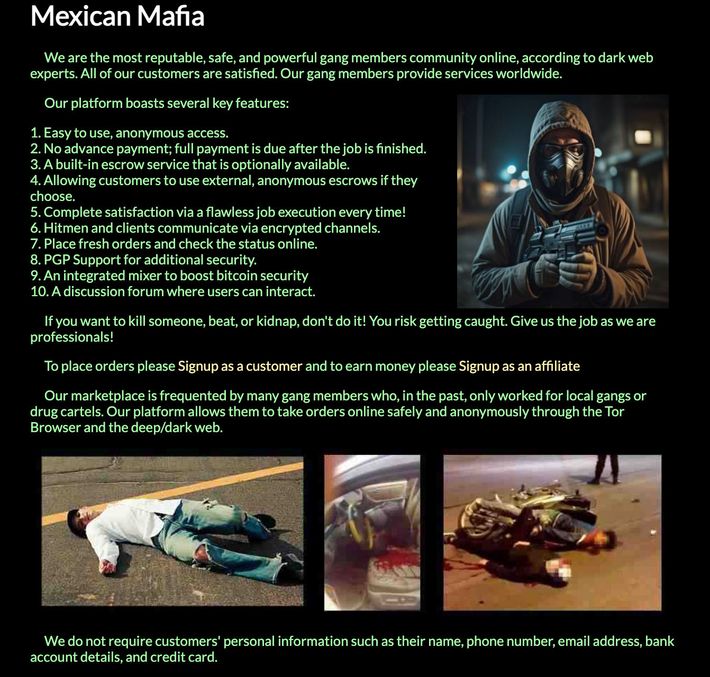

At the same time, Christopher was looking into an extrajudicial approach. He learned about Tails while reading about Edward Snowden, who used the operating system to hide his activities from the National Security Agency. In July 2021, with the software running, Christopher called up Ahmia, a darknet search engine, and looked for a website offering to connect customers with assassins. He settled on a site called the Sinaloa Cartel Marketplace.

Christopher created an extravagantly cryptic username, mjd210eKd69BxG4IsJD, and began messaging other users. “Good day Admin! I have a couple targets—husband wife—that I am needing removed,” he wrote. “However, it is known that they and I don’t quite see eye-to-eye on something. I am a couple days away from submitting the job as an ‘accident,’ but before I do, I was wondering, in your experience, even if it is an obvious ‘accident,’ what kind of investigation will be run against me, knowing that we are not on the best of terms?” Two weeks later, Christopher transferred $16,000 worth of bitcoin and submitted orders to kill the Corderos.

Christopher and Michelle Pence hadn’t planned on having an enormous family. They met as teenagers in a community just north of Seattle and married in 1999, when Christopher was 19 and Michelle was 20. The next year, Michelle gave birth to twin girls. Christopher’s dream was to make a fortune in finance and real estate and live in a penthouse in downtown Seattle. He imagined Michelle would have her own high-powered career. After she became pregnant with their fourth child, he had a vasectomy.

Christopher had been raised religious, and in his mid-20s he began to lean more on his faith for guidance on life’s biggest questions. He thought less about his career and more about his higher calling. “God changed my thinking about how a man is to be the leader of his family and how children are actually blessings and rewards,” he said in a speech at his church. “There are many biblical examples about how our dreams may not be what God wants for us. Job did not want his children to die or his storehouses to be destroyed or his health to be impaired, but God’s perfect will allowed this to happen. Jeremiah wanted to marry a nice girl and have a family, but instead God used him as a prophet of death.” Exactly one year after his vasectomy, Christopher had it reversed.

Michelle documented the family’s life on a blog, and she described how her sense of self, and her role in her marriage, changed as she read books like Created to Be His Help Meet and The Power of Motherhood: What the Bible Says About Mothers. “I entered marriage thinking of it as an equal partnership, knowing but not understanding what it meant that my husband is my head,” Michelle wrote. “I had NO idea the importance of my role as a mother, and the significance God placed on motherhood. I had no idea that God called barrenness a CURSE, and children the greatest blessing he can bestow. I had no idea that God said so much about children in the Bible, they are heritage, a REWARD, a blessing, precious little lambs, arrows in the hands of a mighty warrior and so much more.”

The Pences came to “trust God to open and close the womb as He sees fit.” By 2017, Michelle had given birth to ten children. One died at five months from sudden infant death syndrome; there were also several miscarriages. Another child was born with cerebral palsy. Needing space, the family had gone to live with Christopher’s parents in a semi-rural town 25 miles northeast of Seattle. They turned their property into a homestead with gardens, beehives, dogs, chickens, turkeys, a lilac-crowned parrot, and a succession of cows named Steak, Dinner, Beef, Burrito, and Norman. The kids slept in bunk beds, and everyone traveled to appointments and church in a short bus.

Michelle chafed when doctors advised her to stop having kids; when a social worker questioned her ability to effectively homeschool a child with a disability; when someone at the grocery store casually remarked on the size of her family. She was passionate about educating her children herself and valued, above all, the freedom to teach a curriculum focused on the Bible. The Pences considered the text a straightforward account of history, and every morning, before sunrise, Christopher led the family in studying Scripture.

To Michelle, Christopher was “the handsome man who makes it all happen around here” and “a fantastic example of loving me as Christ loved the church, even when I am very much unlovable.” He was the breadwinner and had a succession of technology-related jobs, including managing a computer store and working as a network architect, before landing a job at Microsoft. Michelle described him with devotion as “a great priest, prophet, provider and protector for his family” who “truly lives out what it means to be a follower of Christ, to deny himself and live for his God, and his family.”

Even as they continued to have children, the Pences wanted to accelerate the growth of their family through adoption. They were motivated in part by religion, believing that the process was a form of “making the same commitment to a child (or children), that God made to us … to take us in our filth, our sin, our depravity, and bring us to a place of being a beloved child.” But the choice was also deeply personal. Michelle came from a troubled home. She had met her father only three times. She was one of six half-siblings, all from different fathers, who were split up by the foster-care system. “I know all too well what loss, abandonment, neglect, and abuse do to a child … because I was that child,” Michelle wrote around the time she and Christopher began submitting applications. They hoped to adopt an entire “young sibling group, who are having trouble staying together because of size,” she wrote on one listings website, adding that they would not mind remaining in contact with the children’s biological parents.

The Pences worked with traditional agencies, submitting to hours of training, interviews with social workers, psychological reviews, and home studies. Opportunities in Colombia and Florida didn’t pan out. One organization blocked them from adopting a group of five siblings because the Pences already had children of similar ages — not optimal, in the agency’s view.

After a few years of dashed hopes, Michelle gave birth again in 2018. That September, taking advantage of Microsoft’s six-week paternity-leave policy, the Pences packed into a motor home and headed east. They saw the Mammoth Hot Springs, worked a miniature Model T production line at the Henry Ford Museum, and stood on a beach in Acadia National Park while the Atlantic rushed over their feet. At some point along the journey, Michelle logged on to a message board for parents with large, homeschooled families. A mother of six in Massachusetts had posted that she and her husband were looking for someone to take care of their children temporarily while they worked through some marital issues. Michelle sent her a message.

The woman, Christina Cordero, and her husband, Francisco, were struggling. They’d had a single-story, four-bedroom house in Chicopee, in Western Massachusetts, but had recently sold it and moved into an RV. Their oldest child was developmentally disabled, and finding adequate housing “proved impossible with such a large family,” Christina told me in a Facebook message. Cisco, as her husband was known, could only find work as a temp. “I was offering six months rent up front, but no landlord would consider us.”

Cisco had personal problems that compounded their troubles. He admitted to the authorities at one point that his sexual behavior was a continuous challenge for his family. He had fought an addiction to pornography since he was a teenager, and the Massachusetts Department of Children & Families (DCF) had investigated him for looking at child porn and showing sexual images to his children. He denied the allegations, and the state took no action.

The Pences arranged to visit the Corderos at their RV in Massachusetts and pray with them. Christopher Pence later said that when they arrived, Christina confided that she didn’t think her children were safe with Cisco. (Christina disputes this.) The Pences said they were open to taking them but suggested that Christina mull it over while they continued on their road trip. When the Pences traveled back through Massachusetts a few days later, the Corderos said they wanted to go through with the arrangement.

The two families agreed on a plan for the next few months: The Corderos would keep their child with special needs while the other five went to live with the Pences. The Corderos signed a caregiver-authorization affidavit, a notarized contract that granted the Pences the right to make medical and educational decisions for the children. And then the Pences, their children, and the five Cordero children all crammed into the motor home and left. Christopher Pence later said, “We got to Massachusetts with ten children and left there with 15.”

Almost immediately, it became clear that integrating the five Corderos, ages 1 to 9, with the Pence kids, who spanned from less than a year old to 17, was going to be awkward. In Mount Vernon, where they stopped to visit George Washington’s estate, an employee asked if they were all one big family. One of the Pence girls answered “yes.” Then a Cordero child interjected: “No, there’s ten of them and five of us, and they took us from our parents in Massachusetts.”

On the way back across the country, the Pences stopped at the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky, where the exhibits show humans coexisting with dinosaurs. They also dropped by Ark Encounter, where the entire group posed for a portrait in front of the doors to a model of Noah’s Ark. In the photo, Christopher and Michelle, who were still in their 30s, could just as easily have been the eldest cousins bookending an extended family photo instead of the parents and guardians of the 15 children huddled between them. Most of the kids seem upbeat despite the long hours on the highway. One of the eldest Pence daughters has her youngest sibling strapped to her chest. On Christopher’s back, in a baby carrier, is the youngest Cordero child, his face fixed in an observant gaze.

The ad hoc nature of the arrangement drew the attention of the child-welfare system. According to police records, soon after the Pences returned to Washington, a deputy with the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office performed a welfare check at the request of the Massachusetts DCF. “All were healthy and appeared happy … home is large and very clean … Michelle is researching how to obtain financial aid for kids as she has been paying out of pocket for their care,” the deputy wrote in his report.

Michelle was feeling stressed, though, and she used her blog to vent about her new reality. “Keeping everyone busy has been an essential around here because the Corderos miss their parents like crazy!” she wrote. She seemed frustrated to realize how different the Cordero children were from her own and overwhelmed by the behavioral problems that followed the siblings’ abrupt separation from their parents. Michelle wrote about the newfound “disharmony” in her house and “epic proportions melt downs”: “Never have we had anyone struggling with sharing, and now it is a huge problem. Never have we had anyone seeking to undermine anyone else or using the level of sharp words and unkind attitudes that we see here now. Never have we seen anyone give an eye roll before this experience … Not to mention the screeching, yelling and whining that accompanies the above.”

Ten days before Thanksgiving, Michelle announced that each night, the children would have to say one thing they were thankful for before they could eat dinner. “We had tears and one saying that she wouldn’t be able to eat until after Thanksgiving because there was nothing to be thankful for,” Michelle wrote. “I am thankful that my bio children are able to help show others how richly blessed we are even when life isn’t going how we want it to.”

As Christmas approached, Michelle and Christopher gathered the children to play a game that would teach them about labor and wages. They explained that sometimes, wages are good. (The wages for making beds that day was lava cake.) Other times, wages are levied for wrongdoing. (The Bible says the wages of sin is death.) They asked the children to talk about the sins they had recently committed; they then announced that the wages would be either $10,000 per child or the loss of their Christmas presents. Some of the children “thought we were joking,” Michelle wrote on her blog. “But we finally got it across that we were not. Anyone who couldn’t pay the penalty would have no Christmas.” Then Christopher stood up and said he would pay for the children. Michelle wrote: “Because of his great, willing sacrifice, everyone else will get presents, but Christopher will not. We made the comparison that Jesus took our sins upon himself and paid the penalty for us.”

At some point, the Corderos and Pences agreed to extend their temporary custody arrangement. The Pences decided that their home, at just 1,900 square feet, was not large enough. Christopher took to Zillow. Microsoft allowed him to work from anywhere, and he found a 4,150-square-foot house on eight heavily wooded acres in Hawkins, Texas, for $325,000. They moved in June 2019.

During this period, according to legal filings, the Corderos were under investigation by the Massachusetts DCF. It is unclear what the agency was looking into, but the Snohomish sheriff’s office attempted at least two additional welfare checks on the children at DCF’s request. The agency eventually told both families that it intended to take custody of the Cordero children and bring them back to Massachusetts, where they might be split up in foster care. (A spokesperson declined to comment.) To keep the siblings together, the Corderos and Pences agreed to make the adoption permanent. In December 2019, the Pences traveled back to Washington to go before a judge and make it official. A picture from that day shows the Pences with all 15 children smiling broadly as they crowd together behind the judge’s bench.

The Corderos had made three cross-country trips to visit their children — twice in Washington, once in Texas — and knew they could not afford to keep doing so. They decided to move to Texas as well. “It was the logical step,” Christina told me. But it unsettled Christopher and Michelle, who started to feel that the Corderos were using them to hide their children from the Massachusetts child-welfare system. Christopher later claimed that the Corderos asked if they could permanently park their trailer home on the Pences’ property. (Christina told me she had asked to park there only during sanctioned visits.) Eventually, the Corderos rented a space at Good Luck RV in Dallas, a two-hour drive from the Pences’ home in Hawkins.

The Pences had a series of difficult conversations with their newly adopted children. One was especially excited that Christina and Cisco had moved to the same state because he thought he would see them more often. “That was a little challenging to work through — that no, even though your birth parents are in Texas, they can’t come over any time they like to, because we need to maintain structure and order to family life,” Christopher said. The Cordero children were also wounded by the fact that their parents were continuing to have more kids. A few months into the arrangement with the Pences, Christina gave birth to a seventh child, and in Texas they told the children they were expecting an eighth. “The oldest girl, she’s kind of hurt that they would have more children after giving up five,” Christopher later said.

Everything was in flux. After little more than a year in Texas, the Pences were ready to leave. The eastern part of the state felt like something out of Exodus with extreme weather and scorpions in the bathtub. “Everything down there is trying to kill ya,” Christopher said. “Bugs, snakes, spiders. We got to the point where the children couldn’t really play outside much.” He went back to Zillow and found a seven-bedroom house in Cedar City, Utah, and purchased it for $659,000 in November 2020. Soon after they moved in, Christopher’s sister visited and took pictures of the entire family playing in the snow, including a newly born 11th biological child.

The Pences never shared their new address with the Corderos. When the five adopted children sent mail to their birth parents, the Pences wrote in a post-office box for a return address.

It is not entirely clear why Christopher Pence wanted the Corderos dead. In Utah, he quickly convinced the family’s new pastor, Jeffcott, that both Christina and Cisco loomed over their household like specters. “They really were creating problems for the children,” Jeffcott told me. “I mean, wetting the bed — just really bad consequences from exposure to the birth parents.” But the Pences’ concern was vague. It also did not seem to involve fears of sexual abuse. Christopher considered Cisco a Lothario but did not think his behavior in that regard involved the children.

A turning point apparently came in May 2021. The Pences returned to Texas to meet with the Corderos. After that meeting, according to Christopher, one of the Cordero children claimed to have seen bruises on the arm of her eldest sibling, the one with developmental problems; when asked where the bruises had come from, he claimed Cisco held him down. (Christina disputes this.)

Two months later, Christopher logged on to the Sinaloa Cartel Marketplace. He spent weeks lingering on the site, looking closely at its FAQ, which offered half-baked answers to questions like “Could this be a honeypot operated by law enforcement?” and “Do you murder children?” (The answer to the latter: “Yes.”) At one point, Pence created a new thread to ask other users if the site was real or a scam. Sinaloa Cartel Marketplace listed rates that ranged from $5,000 to $200,000, and Christopher wrote the administrators to get clarity. Seeing as his targets lived at the same address, could he receive a discount? Christopher also wanted to be sure the hit man knew the Corderos lived with three children: “I am really trying to avoid them from being hurt. I’m wondering if a mugging-gone-wrong might be an option. Or maybe you have another suggestion? One of the children is 13 or so, but slow, so maybe his testimony could help avoid scrutiny/investigation.”

Two site administrators provided short responses. In late July 2021, Christopher began transferring bitcoin into an escrow account and, eventually, ordered the hit. He entered Christina and Cisco’s address and attached photos of the couple he had taken from their biological daughter’s baby book.

Hours later, Christopher messaged the administrators that he wanted the murder order canceled. The next day, he resubmitted it, repeating his request to “please make it look like an accident, or a mugging-gone-wrong, or something of the sort.” In the days to come, he sent a flurry of messages asking for some confirmation that the Sinaloa Cartel Marketplace had received them. He never heard back.

Six thousand miles away from Cedar City, somewhere in Romania, a small band of internet scammers got a payday. Since at least 2016, the group had run a stable of sites on the dark web, including Sicilian Hitmen and Yakuza Mafia, offering bogus murder-for-hire services. They took money from users who wanted people killed, but they never acted on the jobs. The mastermind behind the operation was a fraudster who went by the name Yura. In 2022, at the urging of the United States, Romanian authorities reportedly arrested Yura and his crew, but it’s unclear if they were ever prosecuted.

Yura claimed to Wired that he is an FBI informant. Whether or not that’s true, law-enforcement agencies have gotten a detailed view into his operation and its thousands of clients thanks to the efforts of Chris Monteiro, a British hacker. In 2016, Monteiro discovered a vulnerability in one of Yura’s websites that allowed him to scrape its data, including direct messages and payments. Since then, he has used similar techniques to repeatedly intercept the network’s traffic and feed it to governments and journalists.

“There’s a lot to say about what I’m doing. Is justice being done? Is it good? Probably. But also, could it be done better? I think so,” Monteiro told me over Zoom, sitting at his workstation in the living room of his South London flat. He is in his early 40s, and his long hair was pulled back in a ponytail. He wore a T-shirt that read “THERE. Now I’m not naked anymore.”

Even though the hit men are fictitious, the danger is real. In 2016, Stephen Allwine, a Minnesota IT specialist and a deacon at his church, paid at least $6,000 on a Yura site to have his wife killed; after the hit failed to happen, he murdered her himself. (Allwine is serving a life sentence.)

Monteiro doesn’t always send tips directly to law enforcement because he finds investigators can be put off by the complexity of the cases and the fact that they’re based on hacked information. But in 2021, he managed to get the FBI’s full attention. Monteiro was working with a podcast-production company on a murder-for-hire program for the BBC. The show’s producers began feeding the FBI details of murder orders that Americans were placing on Yura’s sites. Agents arrested a woman in Wisconsin who had tried multiple times to hire someone to kill her ex-husband; a physician in Spokane who wanted someone to take his estranged wife hostage; a man in Tennessee who sought to snuff out his wife; and an accountant in Tampa who paid $12,000 in bitcoin to kill her ex’s new spouse.

On September 2, one of Monteiro’s tips landed on the desk of Brian DeCarr, an agent in the FBI field office in Albany. The Corderos were now living in nearby Hoosick Falls. The next day, DeCarr drove out to tell Christina that someone was trying to kill her. When she found out that Pence was a suspect, she couldn’t believe it. She and Cisco had plans to visit the Pences in Utah at the end of the month; they were supposed to meet at the Hogle Zoo in Salt Lake City. “I was like, ‘No, there’s no way,’” she said. “‘Please make sure my children and their adoptive family are safe, because whoever wants me dead might go after them too!’”

On October 27, exactly three years after picking up the Cordero children in Massachusetts, Christopher Pence’s alarm went off, as always, at 5:55 a.m. Lights flicked on, first in his en suite bathroom as he left Michelle in bed to nurse their infant daughter, then in the rest of the house as he woke his children in turn. He gathered most of them on the first floor for Bible study. (The three oldest Pence daughters were spending the year at Jackson Bible College in Wyoming.) They took a moment to sing “Happy Birthday” to one of the children and said an opening prayer. Twenty minutes later, there was a loud bang on the front door. At the same instant, the house was flooded by emergency lights.

Christopher opened the door to see a black shield and more than a dozen officers wearing body armor, some holding assault rifles. “It felt like Armageddon had come to my front door and I was the only one standing in the way,” he later said.

If Christopher knew why the FBI was there, he didn’t show it. A few minutes later, he agreed to speak with DeCarr in the privacy of a Chevy Tahoe parked in the driveway. The sun was still hidden behind mountains to the east and the temperature was near freezing as the men got inside. Chris Andersen, a Utah-based FBI agent, climbed into the back row while DeCarr and Pence sat side-by-side in the middle.

“I’d love to know what’s going on,” Christopher said as a recorder captured the conversation.

“You’re not under arrest at all. That’s not what we’re doing,” DeCarr replied. “You’re under no obligation to talk to us. We would appreciate your help, okay?” They started by asking Christopher about his job at Microsoft, life in Washington, his marriage. Shy by nature, Christopher seemed almost to enjoy the agents’ company, talking as if they were three dads standing around a grill on a Saturday afternoon. How much did Christopher pay to pave this driveway? Do the AC units on top of the motor homes need Freon? Does Christopher plan to fix up the ’66 Mustang sitting over there? Did he catch babes in that thing?

Christopher seemed especially interested in telling the agents about the adoption. “Do you want the long story or the short version?” he asked them. “Give me the long one,” DeCarr said. Pence described his and Michelle’s desire to adopt, the road trip to Massachusetts, locusts in Texas, how the Corderos became too big a presence in their lives. The agents seemed sympathetic to Christopher’s frustrations. As the sun came up and warmed the Tahoe, Christopher unlocked phones and provided passwords to his computers and tablets.

After about 90 minutes, DeCarr presented Christopher with a mountain of electronic evidence connecting him to the murder-for-hire payments. “You are the protector of these kids, okay? You are the savior of these kids, and you do this for the family. And it’s clear to me — I didn’t understand why before — but it’s very clear to me that you would do anything for these children,” DeCarr said. “What got you to the point where you felt like you needed to have them killed?”

Christopher fought back tears. His deep voice splintered. “On more than one occasion the children have been abused, um, through discipline, through the birth parents …” Gasping and choking back sobs, he strung together half-allegations against the Corderos and again tried to come up with an answer.

“You were doing what you had to do,” DeCarr said. Satisfied he had a confession, he read Christopher his rights and exited the Tahoe to call New York for an arrest warrant.

Even after it was clear the FBI had deceived him into talking, Christopher thanked the agents for “doing what you’re doing.” He continued to be unfailingly polite, exuding the same eerie cheeriness that tinged his messages on the murder-for-hire website.

As they waited, an officer marveled at the children inside Christopher’s house, who were playing music and helping cook breakfast. “Maybe there is something to be said about not letting all the outside influences corrupt their minds, right? I mean, I don’t know what my daughter would do without TikTok on her cell phone,” he said. Christopher laughed.

DeCarr returned to inform Christopher that he was under arrest. “Have I ruined my life?” he asked.

In late 2023, Christopher Pence pleaded guilty to one count of soliciting murder via the internet. Christina told me that since Christopher’s arrest, Michelle has refused to allow her or Cisco to have any contact with their biological children. In April, however, the Corderos got a brief glimpse at Christopher’s sentencing. Their kids were seated with Michelle as if in support of the man who’d tried to have their biological parents killed.

At the hearing, which was held in Utica, U.S. District Judge David Hurd said he was troubled by how much the case stood out from past murder-for-hire affairs he’d seen. “Each one involved a defendant who was a longtime criminal, who had a bad record, and it was not particularly surprising that he or she would hire somebody to kill others. This case is different,” he said. “It’s a very difficult case.”

Hurd sentenced Christopher to seven years. He could be released from prison toward the end of 2028. He will have missed 112 of his children’s birthdays, but at 48, with his youngest child just 7 years old, he could have a lot of fathering left.

Whether he will be allowed to leave prison and pick up where he left off, fathering his adopted children, is complicated. Michelle and Christopher are still the children’s legal guardians, but it would take one phone call to child welfare upon his release to trigger an investigation into the safety of the children under his care. Such an investigation is unlikely to consider that Christopher’s purported motive for committing the crime was the children’s welfare. If a judge believed the children under Christopher’s care were in danger, they could place the underage kids, both biological and adopted, in foster care. Just as likely, a judge could give Michelle an ultimatum: the kids or Christopher.

For the time being, Michelle is caring for all of the children. When I called her on a recent school day, she declined to speak with me, saying there were too many demands on her time. (She didn’t respond to follow-up requests or fact-checking queries.) She tried, briefly, delivering groceries and now depends on donations from the Cedar City community. A few of her children have found work at a small manufacturing plant in town. “For now the plan is to continue homeschooling. For now the plan is to keep things as stable as possible. For now the plan is to take the next step in faith and accept the grace God gives at each turn,” Michelle wrote on Facebook shortly after Pence’s arrest. “God is good all the time.”