Michael Cohen was at home on the afternoon of Thursday, May 30, in his tenth-floor apartment at Trump Park Avenue, a building still managed by the family company belonging to the man he once called “the Boss.” He was sitting on the floor in the living room, his back against the couch, watching MSNBC with his wife and daughter. He held his breath as he waited to hear the verdict. His face was frozen. Eyes wide. Mouth open. Host Ari Melber delivered the news: “Count one … Guilty.” Cohen let out a wild sound, as if half-man and half–rescue animal, a hoot and a growl and a howl all at once. “WwwwwOOOfugh!” His expression turned awestruck. Melber continued, “Count two … Guilty.” Again: “WwwwwOOOfugh!” His heart was beating hard now, so hard that you could almost see it through his shirt. “Count three … Guilty.” “WwwwwOOOfugh!” His wife and daughter laughed, cried, and applauded. “Count four … Guilty.” “WwwwwOOOfugh!” “Count five … Guilty.” “WwwwwOOOfugh!” He balled his hands into fists, punched the air, and cried out, “Yes!”

Inside a stuffy courtroom in lower Manhattan, Donald Trump was having a more contained reaction to the news. He looked downcast as he absorbed the 34 lashes of the verdict. The judge, New York State justice Juan Merchan, then briskly went through the formalities of conviction: polling the members of the jury to check if they were truly unanimous, scheduling a sentencing hearing for July 11, and ordering up a report on Trump from the Probation Department. He released the convict — the certain Republican nominee for president — back into the free world on his own recognizance.

Four miles north, a few blocks from Trump Tower, a smile flickered across Cohen’s face. He had been there — crushed beneath the heel of the system. It seemed only just that Trump should now feel its weight too.

He had hoped that Trump’s conviction would mean his own vindication. For weeks, the defense had campaigned against his character and other witnesses had needled or knifed him on the stand. “He said he was a lawyer,” testified Jeffrey McConney, a former Trump Organization colleague, his voice rich with disdain. “He liked to call himself ‘a fixer,’” Hope Hicks told the court, “and it was only because he first broke it.” Her testimony particularly stung and enraged Cohen. Inside the Trump Organization, Cohen had been perfectly happy to play the bad guy, and he was perfectly happy — often even proud — to recollect his bad-guy past. But testimony that suggested he was bad at being the bad guy? That was too much for him to take. Cohen was still a Trump man at heart. He couldn’t stand the idea that others close to Trump, who saw the world as he once had — divided simply between winners and losers — had thought him a loser all along.

The defendant left no doubt about where he stood. On social media, Trump called his former henchman a “jailbird” and a “sleaze-bag.” In rebuttal, Cohen called Trump “Von ShitzInPantz” and a “Cheeto-dusted cartoon villain.” Inherit the Wind it was not. Some TV commentators argued that Cohen was such a lowlife, and his testimony so unreliable, that it threatened the prosecution’s case. Trump’s lead attorney, Todd Blanche, used the phrase “Cohen lied,” or some variation of it, more than 60 times in his summation. Cohen, according to Blanche, was reasonable doubt personified. If the jury had ended up deadlocking over a Trump verdict, as the defense was hoping, then it was Cohen who would take the blame for the mistrial. So the unanimous guilty verdict came with a sense of release and revenge. They were even: both officially convicted felons. The loser had won.

Still, on some level, Cohen regretted his betrayal. He had not had a choice, as he saw it, but he wished that he had, that Trump had not forced him into the role of enemy. He wished that he could have stayed in his good graces, continued to serve as personal attorney to the president of the United States, continued to work as an extremely expensive Trump-world consultant trading on his connections to the administration. Cohen had spent a lot of time thinking through the endless counterfactuals. Even if he believes, as he says he does, that Trump is dangerous, that he’s bad for the country, bad for humanity, and that in fact we have not yet seen just how bad things will get — that if he’s elected again, the country may not survive — Cohen would take it all back if he could. In a heartbeat, he would accept an alternative reality in which he was never put in a position to become the witness who helped convict the first U.S. ex-president ever to be criminally indicted. He didn’t buy it when people said that in such a reality, his life would be much worse. He might have gone to prison anyway, like so many others who remained loyal to the Boss. But Cohen dismissed lines of thinking that complicated his regret.

On the floor of his apartment, with MSNBC still droning in the background, the smile Cohen flashed dissolved fast, replaced by a worried look. Smiling didn’t feel quite right. He wondered: Was it safe to smile now? Could he even wear a smile comfortably? He wasn’t so sure.

A few hours later, he took the elevator to the lobby of the apartment building, walked over the Trump seal engraved in bronze on its marble floor, and went out through the front door. Trump’s name loomed overhead from the gilded awning. A media scrum had formed on the sidewalk upon news of the verdict. The journalists lurched in his direction, pointing recording devices and microphones and cameras. He stared straight ahead, waving them off, and boarded an idling black SUV. As he tried to shut the door, a reporter wedged his body halfway into the vehicle. He pleaded with Cohen for a sound bite, a word, anything. Cohen declined and politely wrestled the door shut. The reporter knocked on his window. Others followed, making contact with the car as it rolled away.

In the quiet, Cohen exhaled. For a few blocks, he was quiet, too. He wore a dark blazer, dark pants, and dress shoes. The stress of the trial had taken its toll and he had lost 30 pounds. When people told him he looked good, he was offended. He had not been doing well, and he was not happy when the evidence of suffering worn on his body was seen as anything else. “I look horrible,” he would shoot back, correcting the compliment. His face, with its marsupial features, was sunken. He looked out the window at nothing in particular. Finally, as the car passed St. Patrick’s Cathedral, he spoke.

“I thought I would feel differently,” he said. He had expected something approaching peace or happiness or at least some catharsis, a reprieve from the darkness and anxiety that had consumed him, in a variety of ways and with varying degrees of totality, since 2018, when he turned against Trump, decided to cooperate with prosecutors, and pleaded guilty to eight federal felonies. The list of charges included tax evasion, making false statements to banks and Congress, and campaign-finance violations related to a $130,000 hush-money payoff to Stormy Daniels — the same transaction at the heart of Trump’s Manhattan trial. On cross-examination, he had referred to this process as “my journey,” therapy-speak that Blanche seized on and ridiculed. (“Well, the journey you have been on, at least for the past few years, has included daily attacks on President Trump. That’s part of your journey, right, sir?”) But Cohen really did feel as if he had been traveling somewhere, and now that he had reached his intended destination, he was hollow.

“It’s hard to believe that after six years, after everything I’ve been through, that the journey is complete.” He let out a one-note laugh. “It’s unbelievable that this is the first time in his life that he’s been held accountable for anything.”

The SUV pulled up at 30 Rock, where he was set to appear on MSNBC. Back in 2018, when Cohen’s residences and offices were raided by the FBI, the network’s hosts had greeted the news with breathless anticipation. Cohen testified at trial that in those same moments, he was alone and despondent; other witnesses said they feared he would take his own life. Six years later, though, Cohen and the liberal media were on the same team. As Cohen walked across the Peacock-print carpet and made his way to security, MSNBC’s biggest stars — Melber, Chris Hayes, Nicolle Wallace, Rachel Maddow, Joy Reid — were locking in upstairs for a night of special coverage. Cohen offered a friendly greeting to the guard as he removed a fig-size coin, a good-luck charm from a fan, from his pocket.

Upstairs, the mood around the greenroom was giddy. Maddow sprinted through the hallway, her show notes in hand. MSNBC had been covering the Trump verdict like the fall of the Berlin Wall, and now it was time to celebrate victory for the good guys. Cohen received a resistance hero’s welcome. As the backslapping and handshaking and congratulating crescendoed, he loosened up, the flash of a smile giving way to a perma-grin and his quiet stare thawing into hyperactive animation. He laughed and joked with the hosts and analysts and reporters and pundits who were by now Cohen’s old friends, even though he first got to know many of them as he helped fight Trump’s war — a sometimes WrestleMania-style spectacle — against the “fake news” media.

“Long day?” Hayes asked.

“Six years,” Cohen replied. “Six. Years.”

He hugged MSNBC host and legal commentator Katie Phang. “I didn’t eat the whole day. I was, like, nauseous,” he told her. “You know what I ate today? I ate one hard-boiled egg.” A producer perked up and offered to show Cohen over to a craft-services table. He eyed the selection with little interest as he made his way to a coffee urn. He drinks it black, no sugar, an order that has become part of his consumable character as described in both of his books. He paced around, coffee in one hand and phone in the other.

Cohen’s attorney, Danya Perry, arrived to join him on the panel. “Everyone was emotional,” she said, describing the moments after the verdict was read. “I think for a bunch of different reasons.” They both proceeded to the makeup room, though Cohen declined a touch-up for himself. As campy and, well, Trumpy as he could sometimes be, he did not possess the showman’s vanity, even if he did think he looked, at present, pretty lousy. Perry had been by Cohen’s side since his release from a federal prison in 2020 and had helped to prepare him for his four days on the witness stand. Compared to those ordeals, this TV interview would be easy, but Perry couldn’t resist giving him some words of caution. “No gloating,” she told him. “No victory lap!” Cohen turned to face her and winked. He was so back. And then he was on.

For as long as he could remember, Michael Cohen had had trouble sleeping. As a kid growing up on Long Island, he was nervous and restless. He lay awake deep into the night, eyes fixed on the ceiling, panicked about mortality. There was no God, he was as sure then as he is now, and that scared him. “I believe when you die, that’s it, and it saddens me,” he said. “There’s no soul. No free will. There’s nothing.” As a kid, he sometimes stole drinks from his parents’ liquor cabinet just to settle himself down. (He now drinks only the occasional Scotch, he says.) When he did manage to sleep without chemical assistance, his mind and his body still could not rest. In a recurring dream, he was Moses. He would sleepwalk through his house clutching a hockey stick in his hand like a staff. “Let my people go,” he would say.

Sleeplessness continued to plague Cohen in adulthood. His coffee dependence didn’t help. Neither did his anxious addiction to work, a condition that only worsened as his conscious hours became consumed with his service to “Mr. Trump.” Cohen was rich before he ever met Trump. His father was a surgeon, and his siblings were all lawyers. He married into a Ukrainian American family in the taxi business and, through taxi medallions and real estate, amassed significant wealth of his own. By the early aughts, Cohen was worth tens of millions on paper (he estimates his net worth peaked at $104 million), and he and his in-laws began buying units in Trump buildings as both residences and investment properties. He first became acquainted with the Trump family when he helped stamp out a condo-board rebellion. He did so well Trump hired him away from a law firm; Cohen became his personal counsel, and Trump became the Boss.

For a decade, Cohen managed Trump’s affairs (business and otherwise), defended him, and drummed up publicity in the papers. In private, he encouraged Trump to pursue the biggest deal of all, the thing he had toyed with doing since the ’80s: running for president. Most people laughed, but Cohen never took it as a joke. He still likes to tell people he possesses “the very first MAGA hat ever made.” It was created by a printing company owned by his sister. When Trump saw the kind of money there was to be made in the headwear business, her services were retired by the campaign and he took the honeypot for himself.

Others who worked with Cohen in Trump Tower couldn’t understand the attraction that held him and Trump together. But Trump kept him around in an office Cohen testified was 50 or 60 feet from the Boss. Cohen was happy to be Trump’s lapdog or, if the circumstances demanded it, his attack dog. Cohen describes their bond as familial, as if he were an unofficial son. He loved Trump, he admits, though there is little evidence that Trump reciprocated his affection. It does seem like he took pleasure in kicking Cohen around like a mutt.

Trump put Cohen on jobs that, in his view, no one else could get done and perhaps no one else would ever want to do, like knocking down invoices from contractors to his unaccredited and financially troubled university. Cohen hired a tech firm to rig an online CNBC poll ranking the greatest business leaders since the network’s founding — and reportedly had the same firm create a sock-puppet Twitter account called “Women for Cohen.” (Cohen’s version is that he simply gave his blessing to one Woman for Cohen who wanted to make the account.) He threatened a reporter who had dug up a divorce-case deposition in which Ivana Trump had accused her husband of rape, then asserted it was impossible to rape one’s wife. In 2016, he ended up handling payments of hush money to women who said they had slept with Trump. Initially, Cohen worked through David Pecker, who was then the chief executive of the parent company of the National Enquirer. But when Pecker balked at paying to silence Stormy Daniels, an adult-film actress who claimed to have had a sexual encounter with Trump in 2006, Cohen took on the task himself, negotiating a payoff and nondisclosure agreement. When Trump hesitated to cough up the $130,000, Cohen decided, Screw it, I’ll do it myself. He used a line of home-equity credit to borrow the money from his bank.

Cohen testified that he expected to get paid back and not just monetarily. In the fall and winter of 2016, as leaders of government, law enforcement, and business — and also Kanye West — were taking the golden Trump Tower elevators to pay their respects on the 26th floor, Cohen was wondering what place he might have in the White House. It was decided he would leave the Trump Organization, and he believed the president-elect might consider him to be his White House chief of staff, which may seem delusional, but then again, Trump did hire Jared, Ivanka, and Omarosa. Even Cohen seemed to realize that chief of staff was a reach. “To take someone with no political navigations for the role would cause everyone to say it’s a banana cabinet,” Cohen texted his daughter, whom he calls Sami, five days after the election. “I only wanted to be considered because it would help me with my business,” Cohen said. As always, he had monetization on his mind.

Cohen is close with his family. He talks to his parents multiple times a day, and his adult children live with him and his wife of 30 years. This is one of the characteristics that makes his devotion to Trump so hard to understand. Which Cohen knows. It just doesn’t make sense. He was not vulnerable. There was no obvious void he was trying to fill. He had a family who loved him. He had his own fortune. What did he need from a reality-TV star? “Have you ever traveled with Taylor Swift?” he said. (“No” was the answer.) That was all he could think to compare it to. “When you’re at the center of things — when cameras are flashing, it doesn’t matter that they’re not flashing for you.” It was intoxicating. He was intoxicated by it. In any case, his bond with his daughter is particularly strong, and in text messages introduced as evidence in the trial, she is revealed as a sort of sage, acting as a reality check on her father’s ambitions. (She was an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania in 2016.) When the chief-of-staff job went to Reince Priebus, she urged her father to find another role close to Trump in the White House, even if it meant living on a government salary, saying it would give him “unparalleled power for the future.” Cohen reassured his daughter that no matter what, he would maintain his access to the Boss. “I have done so much for him over 10 years,” Cohen wrote, “it can’t be overlooked.”

But in Trump’s world, loyalty ran only uphill. He could be particularly cold-blooded when it came to dealing with his lawyers, whom he treated as blunt, disposable objects. Even his early mentor Roy Cohn — the ferocious model for all Trump attorneys to follow — ended up being cut loose at the end of his life, when he faced disbarment and was displaying symptoms of AIDS. (“Donald pisses ice water,” Cohn complained as he was dying, according to Wayne Barrett’s early Trump biography.) In Cohen’s case, the brush-off came enclosed in a Christmas card signed by the Boss. Cohen opened it, expecting to find a generous 2016 bonus. Instead, he discovered Trump had given him a measly check, far less than the six-figure sum he received most years.

It is worth taking a moment here to consider how catastrophically stupid and shortsighted it was for Trump to stiff his fixer. Had he instead just pulled out his Sharpie and written in a large number — let’s say, hypothetically, $420,000, the amount he later paid to Cohen via a phony legal retainer — then maybe Cohen would have felt appreciated. Maybe Trump could have said with a wink and nudge that they were all square for Stormy Daniels. Maybe there would have been no need for multiple meetings, including one in the Oval Office, to come up with an overcomplicated reimbursement method and thus no justification for charging Trump with falsifying business records. There would have been no incriminating paper trail, and no 34 felonies, just a generous year-end bonus for a valued Trump Organization employee, which would be hard to question considering their very good 2016.

Instead, Trump chose to be mean, in the Dickensian sense, telling Cohen he didn’t matter to him in a language they both understood. Like any other service worker, he would have to fight Trump if he wanted to be made whole for the $130,000 he was out of pocket. Why would Trump treat Cohen so shabbily? Resentment seems to have played a role. David Pecker testified that Trump never liked the idea of paying hush money because he thought, rightly, the truth would come out anyway. Trump had never been ashamed of his womanizing. “I can’t even tell you how many times he said to me, you know, ‘I hate the fact that we did it,’” Cohen told Keith Davidson, the lawyer who represented Daniels, in a recorded October 2017 phone call that was introduced at trial.

On January 10, 2018, Davidson sent Cohen — who had by then settled into a lucrative role as personal attorney to the president — a text. “WSJ called Stormy,” it said. The Wall Street Journal was working on a story about the hush-money payment, which appeared two days later. The agreement began to unravel. A liberal watchdog group filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission, saying that the Daniels payment should be investigated as an illegal in-kind campaign contribution. Cohen told the commission the payment was a “private transaction” paid out of his personal funds.

On April 9, 2018, there was a knock at Cohen’s door. When he opened it, the FBI served him with a search warrant, from which he learned the federal government was investigating him for various financial crimes, including campaign-finance violations. Cohen later testified that, in that moment, he felt his “life being turned upside down.” He left a phone message for Trump. Trump called him right back.

“And he said to me: ‘Don’t worry, I am the president of the United States,’” Cohen testified. “ ‘There is nothing here. Everything is going to be okay. Stay tough.’”

Cohen never spoke directly to Trump again.

After the call, Cohen testified, he resolved to stay “in the Trump camp.” The Trump Organization initially paid for his expensive Washington defense attorney. He also talked for many hours with Robert Costello, a New York lawyer who was close friends with Rudy Giuliani, who was taking control of Trump’s defense in the Mueller investigation. Costello first met with Cohen in a conference room at the Regency hotel on Park Avenue. He later testified that Cohen was distraught and talked about jumping off the roof. Costello offered to open a “back channel” line of communication to Trump via Rudy. Cohen thought it might be an escape route.

Shortly after Cohen met with Costello, Trump posted a series of supportive tweets. (“Most people will flip if the Government lets them out of trouble even if … it means lying and making up stories. Sorry, I don’t see Michael doing that despite the horrible Witch Hunt and the dishonest media!”) Costello emailed Cohen, telling him that the posts were Trump’s way of signaling he was happy the back channel was open. “You are ‘loved,’” Costello wrote, putting the word loved in quotation marks, as if it came from Trump. “Sleep well tonight. You have friends in high places.”

Costello presented Cohen with a retainer agreement, but Cohen never signed it and he never paid the lawyer a penny. He testified that he felt there was “something really sketchy and wrong” about their interactions but said he kept talking through the back channel because he believed that the possibility of a preemptive pardon from Trump was being “dangled.” Still, he assumed that the back channel was meant to benefit Trump, not him. Emails introduced by the prosecution at trial showed that Costello was simultaneously writing to a partner in his law firm that his objective was “to get Cohen on the right page without giving him the appearance that we are following instructions from Giuliani or the president.”

Trump reportedly did consider giving Cohen a pardon but appears to have calculated that the political cost of protecting Cohen was greater than the legal risk of letting him hang. He cut off the subsidy to Cohen’s lawyer in Washington, who quit the case. Cohen started to waver. On June 21, the Trump-hating comedian Tom Arnold posted a photo of himself and Cohen at the Regency, which Cohen retweeted, and then Arnold told reporters they would be “taking Trump down together.”

“What should I say to this asshole?” Costello wrote his law partner. “He is playing with the most powerful man on the planet.”

“My wife, my daughter, my son all said to me, ‘Why are you holding on to this loyalty?’” Cohen said in his testimony. He hired a new lawyer who had no connection to Trump’s legal team and soon agreed to plead guilty. Trump, who was referred to as “Individual 1” in the charging document that described Cohen’s actions in the Daniels case, responded to the plea by tweeting: “If anyone is looking for a good lawyer, I would strongly suggest that you don’t retain the services of Michael Cohen.”

Cohen gave testimony to Congress in which he called Trump a “con man.” Democrats rejoiced over his turn. But the self-described fixer couldn’t keep himself out of prison. Instead of throwing himself on the mercy of his prosecutors, he didn’t sign a formal cooperation agreement and tried to pick and choose where he would help investigators. Because Trump was considered immune from prosecution as president, he had no bigger fish to offer up. Prosecutors wrote a sentencing memorandum to his judge that portrayed him as deceptive and manipulative and accused him of taking a “rose-colored” view of his crimes. The judge ended up hitting Cohen with a three-year sentence. He had tried to flip, but he had flopped. (Cohen says this widely reported version of his plea negotiation is “completely wrong.”)

He spent 13 and a half months in FCI Otisville, a federal prison with a minimum security camp that has tennis and bocce courts. He came to believe he was a political prisoner of the Trump administration, that it was trying to torture him, and that the prosecutors and even his judge were all in on it. While inside, he had started writing a book about Trump. In July 2020, the Bureau of Prisons revoked a pandemic-related furlough after a meeting in which Cohen claims federal officials tried to bully him into agreeing not to publish his book. He was returned to Otisville and placed in solitary confinement in a higher-security area of the prison. (The government claimed Cohen was remanded for “defiant” behavior, not book-writing, and that the solitary stint was a standard COVID quarantine.) According to a subsequent lawsuit Cohen filed against the federal government, Trump, and others, the conditions of his reimprisonment were miserable. For 16 days, he was stuck in an eight-by-12-foot cell. It was summertime, and the poorly ventilated box was broiling. His blood pressure ran dangerously high. (The lawsuit was dismissed in 2022; Cohen said he intends to appeal it to the Supreme Court.)

It was at this dire moment that Cohen found Perry, his current lawyer, who has ended up acting as a sort of spirit guide on his legal journey. A former federal prosecutor, Perry took on Cohen — first at a steep discount and then, when the $200,000 raised for his defense by supporters ran out, as a pro bono client. She filed a petition to get him back out of prison. A federal judge ended up reversing the decision to re-imprison Cohen, calling it “retaliatory.” He went back to home confinement until his sentence ended in late 2021 and used the time to finish his memoir Disloyal.

Cohen began offering evidence to prosecutors from the Manhattan district attorney’s office when he was still in Otisville and continued to do so over the next four years as the case against Trump stopped and started and pivoted. In 2022, he published a second book, Revenge, in which he questioned why the DA’s office seemed reluctant to bring a case. “You’ve been told it’s my credibility,” he wrote. “I call bullshit. Put me on the stand and let me loose.” The newly elected DA, Alvin Bragg, showed no enthusiasm for unleashing a prosecution that depended on Cohen. In the end, though, Bragg and his team seem to have come around to the wisdom of an old law-enforcement adage: It sometimes takes a small-time crook to catch a world-historical crook.

For Perry, one of the central challenges of trial preparation was persuading Cohen to tame his wilder impulses so he avoided coming off as a madman. An emotional client with a famously hot temper, Cohen required a combination of legal counsel, life coaching, and therapy.

Earlier this year, Cohen and Perry began to meet regularly with a group of assistant DAs who would handle the trial. They would review the case in five- or six-hour sessions in an eighth-floor conference room. Perry would conduct mock cross-examinations, playing the role of Blanche, whom she had known well when she was a line prosecutor at SDNY and he an eager young paralegal and then an assistant U.S. Attorney.

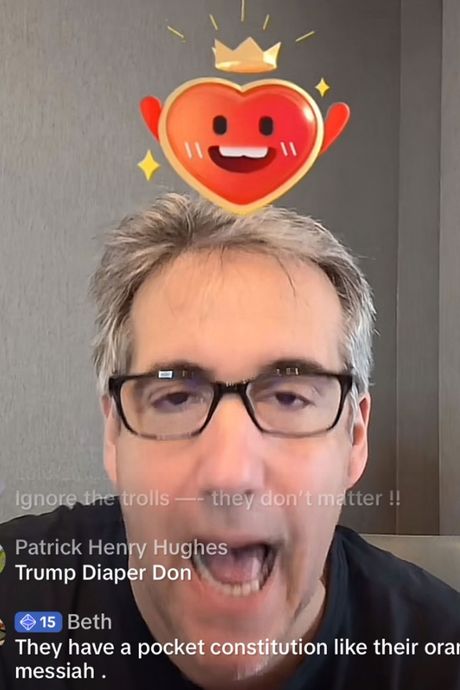

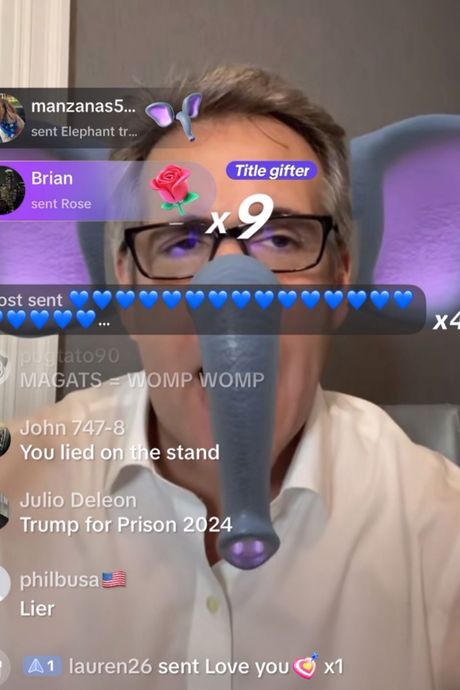

Cohen at times seemed hell-bent on demolishing all these careful preparations. He would at night take to TikTok, yapping about the defendant, sometimes through goofy filters that made him look like a medieval knight or whatever. These shitposts appeared as an unwelcome surprise to prosecutors, who were trying to build a credible case around Cohen, and to Perry. Cohen dismissed pleas to cut it out — he just couldn’t stop himself.

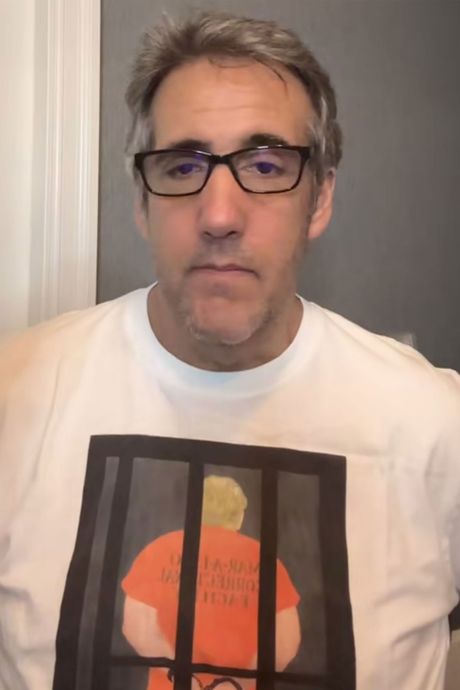

He ended up on TikTok because, as ever, he couldn’t sleep. Late at night, the world would be at rest, and there he was, alone with his nerves in the dark, scrolling on his phone for hours. He couldn’t eat. He drank too much coffee. His eyes were wide. His pupils stayed dilated. His head swiveled at the tiniest sounds. He had the expression of a hunted man. He thought that he really might be. He expected violence to visit him, he said. Sometimes it seemed like he was looking for it. When Trump held a rally in the Bronx during the trial, he considered showing up but thought better of it. On TikTok, he found some community. He didn’t see the harm. He kept swiping up. Before long, he started posting. Sometimes he streamed live. In one such livestream, he wore a T-shirt that depicted Trump in an orange jumpsuit, behind bars. The defense would introduce it into evidence.

At one point, Justice Merchan asked the prosecutors why they couldn’t get their witness to stop, and one told the judge he had “no power” over Cohen. Merchan told him to tell Cohen to control himself, and “that that comes from the bench.”

What finally reached Cohen, he said, was a personal plea: Perry told him that every time he acted out, he made her look like Blanche — another lawyer with an uncontrollable client. He stopped streaming and posting, at least for a little while.

Cohen tried to find other ways to pass the time. He watched cable news until he couldn’t anymore and then he watched true-crime documentaries and a series about Vikings. He spent hours sitting outside at a coffee shop near his apartment, taking meetings or alone and staring at his phone. Sometimes he watched MSNBC live on the device. He said he didn’t like all the attention he received from strangers on the street, but he did come to accept and expect it, and his body language suggested that he yearned for it. When someone passed by his sidewalk table, he would lean his chin forward, angling his face as if to be more visible. Often the person would stop dead in their tracks and exclaim his name or tell him “thank you” or offer a prayer of support. Occasionally, he said, he was heckled or threatened, but if that was happening, it was with much less frequency than he was praised.

One afternoon in May, when he was at the café, two elderly women sitting a few tables away from Cohen began pulling up images of him on their phones. They conferred with each other, confirming they were correct about who they thought he was. One of them then stood up, walked a few feet toward Cohen, and raised her phone in the air, making no effort to conceal that she was snapping photos of him. She didn’t say “hello” or acknowledge her subject at all.

“Ma’am, please,” he said. “Don’t do that.”

She ignored him and continued. He covered his face with his hand.

At last, on May 13, Cohen’s moment came. He and Perry rode down to the criminal courthouse on Centre Street. They arrived early, around 7:30 a.m., and proceeded to a witness room, where they would sit for two hours while the Secret Service locked everything down. During those waiting periods, Cohen’s anxiety spiked. He was operating on no sleep, no food, and no blood-pressure medication, which he stopped taking owing to concerns that one side effect — breaks for frequent urination — would make him look weak in court. Cohen would pace frantically around the witness room, wondering aloud what he would be asked and fretting over how he should respond.

On that first morning, when the prosecutors called Cohen’s name, a side door to the courtroom opened and Cohen walked past Trump, who was sitting sullenly at the defense table. At long last: the Confrontation. But as Cohen went through the preliminaries of his testimony, talking about how he had first come to work for Trump, the defendant’s eyes drooped closed. Like everyone else, Cohen had heard that Trump had been drifting off at times throughout the trial. But even now? “I see him,” Cohen narrated later. “His eyes are closed. His body is thrown back into the chair.” Cohen tried to detect some signs of sentience, some twitches of aggression, behind his eyelids. But he finally came to the conclusion that Trump was unconscious.

“It’s crazy,” Cohen said. “I would say for my very first day, I’m not joking now, 90 percent of the time that I was on the stand, he was sleeping. Well, I shouldn’t say sleeping. He was with his eyes closed and slumped over. Here’s the crazy shit: The jury can see him! They are watching him! Now, if I was a juror and the defendant is so disinterested in his own case? I’d be pissed!”

From the stand, Cohen was able to assess Trump’s face carefully. It was by now familiar in the way that only the face of a family member or lifelong friend could be. He had imagined it, scorned it, and missed it. But now, Cohen mostly felt incensed. He was damning Trump, and Trump was dead to the world. As an insomniac, he felt taunted. “I can’t even sleep in my own bed,” he said. Cohen stared at Trump for long stretches, but defendant and witness made eye contact only once, according to Cohen. It was brief and accidental. “I looked over to my right, and he looked at me, and I looked at him and then he quickly looked away,” Cohen said.

Maybe Trump had just heard it all before. Cohen’s testimony came as something of an anticlimax because the prosecutors had already introduced much of what he had to say through prior witnesses, lessening the risk of appearing to rely too much on the word of a felon. Cohen would often turn to face the jurors when he testified, and he thought he was reaching them. Still, off the stand, he was insecure about his performance. He was angered or annoyed by media personalities whose opinions about the trial diverged from his own.

When it came time for cross-examination, Blanche attempted to bloody him up, interrogating Cohen about financial crimes he had pleaded guilty to that had nothing to do with Trump and suggesting he was making a fortune off his new career as an author and podcaster. (On the stand, he said he made some $3.4 million from Disloyal and Revenge.) But Cohen managed to answer in an even tone when Blanche brought up his previous misdeeds and evasions. “You want to call it a lie?” Cohen replied at one point. “I’ll call it a lie.” When Blanche confronted him with his past insults, he would reply, blandly, “Sounds like something I would say.”

Back at Trump Park Avenue after a full day of cross-examination, Cohen was offended by Ari Melber’s assessment of his performance on the stand. Melber said Cohen was a crucial but imperfect witness who had faced a “winding but relentless” cross. Cohen felt this was “hypercritical” and “unfairly biased” regarding his hourslong testimony. He raged about Melber and fantasized about revenge. He calmed down by repeating to himself, “Michael, stay in your Zen. Michael, Stay in your Zen.” Cohen assumed the role of legal analyst to size up Blanche. He thought Blanche would be a better cross-examiner if he “stayed focused on topics without the relentless, meandering style of questioning.” Cohen went on, “I’m not surprised. I should not have expected more after learning that this is only his second trial as a criminal-defense attorney.”

The following court day, Blanche sprang, confronting Cohen with what was either a major memory lapse or an outright lie. On direct examination, he had testified that he had gotten the go-ahead to pay off Daniels in a conversation with Trump on his bodyguard’s cell phone, and the prosecution had introduced records showing a brief call. The defense had discovered texts indicating that, around the very same time the call was placed, Cohen was complaining to the bodyguard about harassing phone calls from a 14-year-old prankster. For all his hours of preparation, the contradictory evidence was a surprise.

“That was a lie; you did not talk to President Trump that night,” Blanche shouted. “You can admit it!”

“No, sir, I can’t,” Cohen stammered. He later acknowledged he was “caught off guard” but said he “never backed down from what I knew to be accurate,” which was that he had talked about the Daniels deal with Trump during the call. After court adjourned, TV commentators described it as a devastating setback for the DA. Cohen returned to the stand the following Monday, sounding less confident. His voice was so soft at times it seemed like he might be flickering out. Blanche opened by asking him if he had spoken to any reporters over the weekend. He said he had not. “You didn’t speak to a single reporter about what happened last week?” the attorney asked. “I have spoken to reporters who just called to say ‘hello,’ to see how I’m doing, to check in,” Cohen replied. “But I did not talk about this case.” He may have been telling the truth about his conversations over the weekend. As for the days prior, well, some reporters in the court gallery had to laugh.

The defense did its best to demonstrate that Cohen was an unreliable narrator. In his final argument, summoning his inner Johnnie Cochran, Blanche called Cohen the “GLOAT,” or “greatest liar of all time.” But Trump’s attorney never succeeded in making him look like the biggest liar in the courtroom. Cohen was proud of himself for defying all expectations and keeping his cool on the stand, even when Trump’s team tried to confront him with his past false statements. “What I found interesting,” he said on the phone, “is that a lot of the pundits, they all have me as a bombastic, obnoxious, sharp-elbowed loudmouth attorney who’s gonna lose his shit on the first attack by Blanche, and it’s two days in a row they ain’t seeing that. I mean, look, I would be, obviously, funnier on the stand if it was appropriate, but it’s not appropriate.” Cohen took devilish pleasure when the judge, citing a gag order meant to protect witnesses and others from intimidation, held Trump in contempt for attacking him along with Daniels. “Now, if I was a prick, I would start tweeting nasty shit about Trump.” Then, suddenly, he had to hang up: “Oh, crap, it’s Scaramucci — I’ll call you right back!”

The next morning, in a fruitless attempt to remind the jury of the person Cohen was outside the courtroom, Blanche took another tack, questioning him about some rabid-sounding podcast clips.

“You said, and we played it for the jury,” Blanche said, “that revenge against President Trump is a dish that is — ”

“Served best cold,” Cohen said, finishing his sentence for him.

Trump claimed he wanted to testify. And he claimed, falsely, that Merchan’s gag order might prevent him from doing so. In the end, on the advice of counsel, he chickened out. The defense called only one substantive witness, Robert Costello. The attorney had gone on to represent Giuliani and Steve Bannon and had recently called the trial “a cancer upon our collective judicial system.” He was supposed to help to make Trump’s case. His performance was about as disastrous as you could imagine. He was defiant and shifty. Merchan nearly threw him out of his courtroom for displaying contempt. And with that, Trump’s defense rested.

Even so, many commentators were predicting a long deliberation and maybe even a hung jury. “We were never willing to say ‘This is going to be a conviction,’” Perry said. “It was so hard for me and exponentially harder for him. He went from zero to hero. Everyone was like, ‘He’s a liar! A thief! A con man!’”

“Michael has told a lot of lies,” Perry went on, “but he’s been telling the truth for six years about the lies he told. He lied mostly for Trump.”

And he paid for it. Cohen remains deeply disturbed by his experience in prison. He brings it up constantly. If someone complains about something — traffic, say, or a long day in court — he can’t help but shoot back, “Try solitary confinement!” And when he gets that faraway look, when he falls into that trancelike state that it’s hard to shake him out of, he explains this is one of the ways being an inmate transformed him. He can fall into mental recesses, he can stay there, he can forget entirely about his earthly existence, about where he is at that very moment, about the fact that he is sitting at a sidewalk café across from another person as they wait ten or 15 or 30 minutes for an answer to their question. Often, he travels back to the good times with Trump. He admits he still loves him. When it was good, it was great. They had fun. When he remembers, it is as if he were watching a film reel in his head. He describes the scenes slowly. His face is serene. “If I could go back?” he said. He offered the year 2012. He would never have shown Trump polling that suggested he ought to run for president, which he believes was instrumental in Trump’s decision, three years later, to seek the Republican nomination, though the Boss had been publicly floating the idea since 1988. Or how about 2015? Cohen would never have sent Pecker an invitation to a campaign announcement at Trump Tower. He would never have had MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN printed on a hat. “I’d go back further,” he said. To 2007. He would never have gone to work for Trump in the first place.

Still, he couldn’t help but smile when locked in a memory of the good times with the Boss. “At times, I miss him,” he said, “the old Trump.” All of Cohen’s idiosyncrasies, all of the facets of his personality — he fit so perfectly at Trump Tower. It was like he was made for that time and place. The experience was like finding that he possessed a code to unlock some secret power he had within him all along. It was nice to feel so useful and so skilled. And it was, often, a lot of fun. He would, it seemed certain now, never experience anything like it again.

One afternoon after his testimony had concluded but before the verdict came down, Cohen was sitting outside a café with his wife. A friend of theirs had broken several toes in a freak kitchen accident, and they were looking at a photo of the X-ray. Cohen smiled as he peered away. During one stretch in Otisville, he said, he was chained up the whole day, whether he was sleeping or showering. As he tried to maneuver from the top bunk, he lost his balance and came down hard on his toes. He heard them crack. He knew they were broken. But the guards wouldn’t give him medication, nor would they give him bandages to stabilize the bones. Then he received a book someone had sent and ripped the tape from the box and wrapped it around his foot. There. Problem solved. Telling this tale, he beamed with pride as he recalled his own cleverness. He was the fixer, through and through.

He sometimes still wondered whether, if he had been just a little more flexible, he might have been able to fix his relationship with Trump. What if he had stayed on the team, done some time, and kept his mouth shut? He would think about Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign manager, who had been similarly targeted in the Mueller investigation and who had quietly done his time before receiving a pardon. Recently, Manafort has been back to consulting with Trump. Manafort even sent Trump to his own New York lawyer, Blanche, like they were just another pair of old guys sharing tips about urologists. Sometimes, Cohen’s mind reeled forward to the alternative life he might be living if he had stuck with Trump. He said he might be “running the RNC. I’d be on Fox News, Newsmax, OAN …”

Waiting for the verdict was agonizing. Cohen felt the fate of the country was riding on his shoulders. He needed surgery on one of them, in fact, and had been putting it off. That felt just about right. He worried about being killed. If his testimony sealed Trump’s fate, he knew, many Americans would want to hurt him, or his family, and maybe some would come looking. And if Trump got off, millions of other Americans would curse him and say it was all his fault.

Then the jury of anonymous New Yorkers came to their decision. Maybe those 12 people didn’t like Michael Cohen, but they believed him, or at least believed him enough to find the former president guilty of 34 felonies. “All of a sudden, he’s a truth teller,” Perry said. “He’s gone through hell and back. I don’t know if he’s back yet.”

On the night of the verdict, Cohen seemed to have reached a state of, if not contentment, at least temporary satisfaction. At MSNBC, his perceived nemesis Melber patted him on the back, shook his hand, and asked, “How you feeling?” Cohen was cordial, but when Melber walked away, Cohen raised his eyebrows. Vindicated! On the air, he poked back at Blanche, calling him the “SLOAT,” or “stupidest lawyer of all time.” All night and into the next day, his phone lit up roughly every five seconds as the congratulatory notifications came in, illuminating his lock-screen image of the tide rolling out on a sandy beach. Funny, since Cohen hates the beach so much that, like black coffee with no sugar, the trait is part of the story he tells about himself. He doesn’t like the feeling of sand on his skin. Even worse, wet sand. He has a thing about textures in general. And he doesn’t like forced relaxation. He won’t go to spas for the same reason, plus he doesn’t like to be touched by strangers. He physically recoils when recounting instances in which his wife has dragged him to the beach. Asked why he would want to look at an image of a beach every time he gets a call or text, Cohen looked puzzled. “Huh,” he said. “That’s the beach?” He claimed he’d never noticed the beach picture before.

The phone rang again. He laughed. “Can you believe it? Fox News is calling me.” It rang again. Inside Edition. He was back in the game, a winner, and he felt free. “I’ve got 8,000 messages!” he said. He seemed to be determined to comb through them all, even opening obscure inboxes like Facebook Messenger to see what people were trying to say to him.

In the car on the way home from 30 Rock, Cohen answered a call from his mother. “Hey, Mama,” he said. Her voice, with her thick Long Island accent, pierced the car. “I cannot begin to tell you how many people told me you were so great and you should have a show!” she said. Cohen smiled, a different smile this time, not boastful or conflicted. “Yeah, very entertaining, aren’t I?” he said. “Did you like my comment? I called him a SLOAT.” His mother laughed. “Danya — she’s great! I hope she gets very well recognized for her work on this.” Cohen laughed. “She already is. Ron Perlman is her client, and so is Leon Black. She’s a very big deal … Yeah, yeah, I’m on my way home now.” “Well, how did she get home?” Mrs. Cohen asked. “I dropped her off,” Cohen said. “Because I don’t want her walking!” Mrs. Cohen continued. “I don’t want her walking either,” he said. “You taught me well, Mama.”

In the days to follow, there’d be more interviews, more podcast appearances, more offers of thanks from his grateful nation, or at least the half of it that didn’t think he was a rat. Cohen had looked back for so long, and now, finally, he felt like he could plot a way forward. On November 6, the day after Election Day, Cohen said he plans to announce his campaign for New York’s 12th Congressional District seat, running in the Democratic primary against Jerry Nadler, who has held the job for more than three decades. “We thank him for his service, but it’s enough already,” he said. Cohen would have run this year, but the protracted mental breakdown that came with the trial made it hard to plan the launch of a new career as a politician.

Some commentators were warning that in a second term, Trump would turn his Justice Department against his political enemies, but Cohen cites his own experience as evidence that the Boss already did that the first time around. He still thinks about Trump constantly, as much as he ever did when he was sitting 50 or 60 feet away from him every day. “I often think,” Cohen said, “How would the world see me, how would my children see me, if Donald Trump did not view me as expendable?” On cross-examination, he admitted he was “obsessed” with Trump and compared himself to a former member of a cult. But even when he was on the inside, his entire life wasn’t about Trump the way his life in opposition to Trump is now. Cohen managed to get his payback, but he will never be made whole. He could take some perverse pleasure, though, in the knowledge that, maybe for the first time, the obsession ran both ways. On the first morning after the verdict, Trump spoke in the lobby of Trump Tower, where Cohen had arrived each workday for the decade of his life spent in service to him. “I’m not allowed to use his name because of the gag order,” Trump said of Cohen. “He is a sleaze. Everybody knows that. Took me a while to find out.” Hate can be a form of caring. He had to lose everything first, but Cohen was finally on Trump’s mind.

More on Trump’s conviction

- What It Was Like to Sketch the Trump Trial

- What the Polls Are Saying After Trump’s Conviction

- The Courage of Alvin Bragg’s Conviction