This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

(This piece, and our package on Elon Musk, was originally published in August 2022. On October 27, Musk completed the acquisition of Twitter hours before a court deadline that would have required him to go to trial over the purchase. He immediately fired several top executives and tweeted “the bird is freed.”)

In January 2018, Tesla announced details of a new contract with its CEO, Elon Musk, that sounded less like an executive-compensation package and more like the premise of a game show. Under the deal, Musk would take no salary but could earn large bundles of stock options each time he raised the company’s value by $50 billion. If it went up by a mere $49,999,999,999, he would leave empty-handed.

The contract’s top prize could be unlocked only if the company’s market cap hit $650 billion by 2028, a 13-fold increase. Tesla was bleeding so much money — it was among the most shorted stocks on Wall Street — that growing its value that significantly in a decade, or ever, seemed hopeless. The New York Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin described the feat as “laughably impossible.” And then, in December 2020, with seven years to spare, Tesla’s value blew past the target, lifting Musk’s personal net worth to $185 billion and making him the richest person on the planet.

There were lots of reasons for Tesla’s rise, many of them concrete. The company announced it would open new factories in Austin and Berlin. It reported four consecutive profitable quarters for the first time and was invited to join the S&P 500. It grew production to build half a million cars in one year and dominated the U.S. market for battery-powered electric vehicles. It was a pioneering company with incredible potential. Yet the single biggest accelerant — a factor that, today, explains why an industrialist memelord is the dominant figure in American business and culture — was probably Musk’s tweets.

Right after his new contract took effect, Musk started tweeting a lot. He had always been prolific, but this was the point where he went from, by one count, 197 tweets per month (December 2017) to 384 (May 2018), posting Baby Yoda memes and self-produced rap songs, calling a diver who had courageously helped rescue children from a cave a “pedo guy,” and announcing bogus plans to take Tesla private at $420 a share. And then, emboldened by his victory in the defamation lawsuit over his pedo-guy tweet and his light punishment from the Securities and Exchange Commission over his $420 tweet, Musk tweeted even more — 446 times in July 2020.

Whether Musk was making dubious claims about his company’s production capabilities (“1000 solar roofs/week by end of this year”), applying reverse psychology (“Tesla stock price is too high imo”), or hyping other meme stocks on the side (“Gamestonk!!”), Tesla’s stock went up — first by a little and then, during the pandemic, by a lot. His followers spent their stimulus checks on Tesla shares, then they discovered the options market, magnifying the gains. In late 2021, Musk’s net worth touched $315 billion, prompting Forbes to declare him the richest person who had ever lived.

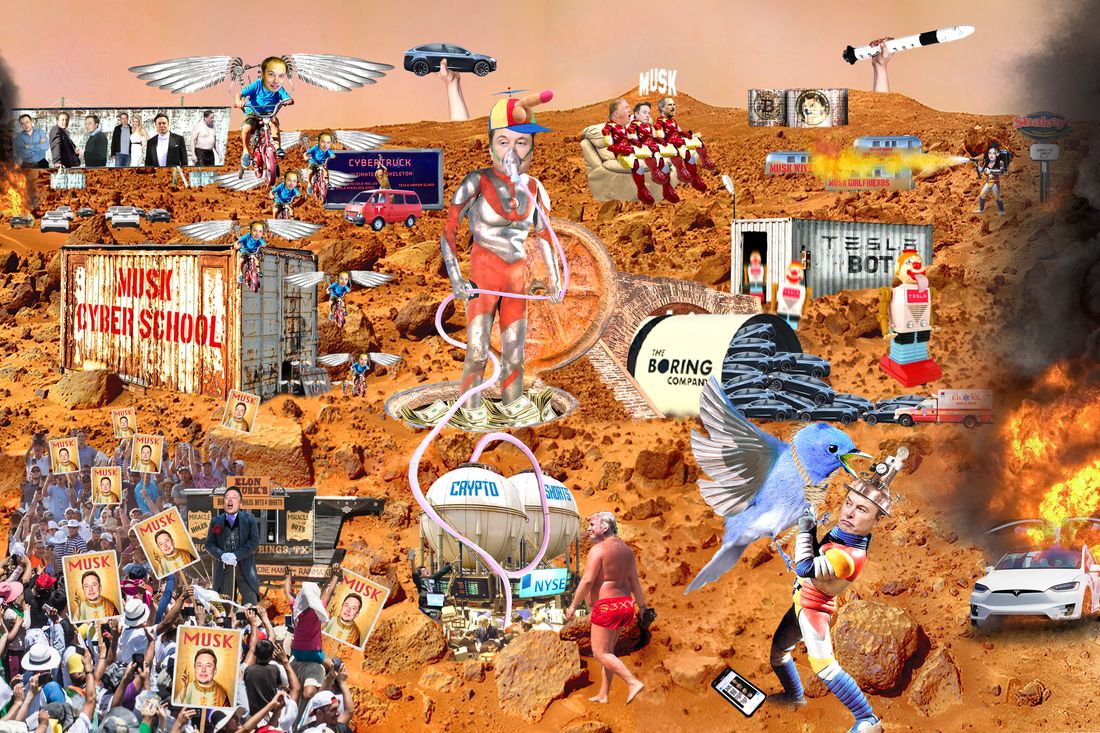

Elon Musk, as understood by …

It’s hard to fathom how somebody could make more money faster than anyone ever has by tweeting, yet that’s pretty much what happened: A carrot was dangled, and Musk, likely figuring he would never reach it on the basis of such old-fashioned metrics as quarterly earnings, yoked Tesla’s stock to his Twitter feed and went goblin mode. A little like when Neo from The Matrix realized that reality was a mirage and therefore he could do kung fu without any lessons, Musk intuited the illusory nature of the stock market and social media and ran up a new all-time-high score. If Tesla might have been a $300 billion company under a generic Silicon Valley CEO, it was a $1.2 trillion company with the guy who turned it into a product cult.

He had always been sui generis, but this is when he became the Elon Musk we know today — a master of atoms, bits, and bullshit who begs our awe, skepticism, and irritation in ever-shifting proportions and whose record-breaking fortune may be only the tenth-most-interesting thing about him. Musk puts a reported 80-plus hours a week into running two major companies, Tesla and SpaceX, with time left over for side projects in tunneling (the Boring Company) and brain implants (Neuralink) — and somehow even more time to host Saturday Night Live, suntan with Ari Emanuel, and spend entire afternoons explaining orbital physics and the limbic system to Joe Rogan. It’s no wonder Musk thinks we live in a simulation, because he definitely lives in one where the normal rules of the universe seem to hold less authority: Newton’s laws, financial regulations, mores of business and celebrity, and soon, he hopes, the legally binding terms of his purchase agreement with Twitter.

In April, Musk made an unsolicited $44 billion bid for his favorite social network. It looked like bad business; the company had lost money for eight of the past ten years. Musk insisted he wasn’t seeking a profit but rather to save what he called the internet’s “de facto town square” from partisan content moderators. “Having a public platform that is maximally trusted and broadly inclusive is extremely important to the future of civilization,” he said. “I don’t care about the economics at all.” But he cared about the economics somewhat when, amid a broader stock slide, Twitter’s value sank by almost a third from what Musk had agreed to pay for it. He then said the sale was “temporarily on hold” and accused the company of misleading him over the number of bots and spam accounts on the platform — though, he hinted, he might be willing to tolerate those extra bots at a discounted price. Twitter declined to bargain, and in July, Musk attempted to terminate his offer. (One theory is that Musk had always intended to bail on the deal and was using it only as cover to sell $8.5 billion of Tesla stock.)

Twitter sued to force Musk to follow through on the transaction, and a Delaware Chancery Court judge has scheduled an October trial. If Musk wins, it may prove he has reached escape velocity from all rules and laws; it’ll also probably decimate Twitter’s stock and leave the company exposed to another hostile takeover, assuming it isn’t incinerated by shareholder litigation first. If Musk loses, he’ll get the cosmic comeuppance of being judicially compelled to buy the stupidest company in the world at something like a $14 billion markup. Whatever the outcome, the Curb Your Enthusiasm tubaist waits in the wings.

Musk has played the troll so convincingly that it’s easy to forget he isn’t just one. Consider his offline skill set, an array of talents heretofore unimaginable outside Walter Isaacson’s most depraved fantasies. Musk’s formal education ended with bachelor’s degrees in physics and economics from the University of Pennsylvania, but his self-taught expertise spans aeronautics, solar energy, artificial intelligence, and other fields. People he has worked with say he combines the abilities of a venture capitalist who can spot and manifest funding for far-off opportunities (such as the potential to power a car with lithium-ion batteries or make cheap rockets that can be launched more than once), an engineer who can help clear the practical hurdles to those opportunities (like designing the body of an automobile or stress-testing rocketry components), a systems savant who can align complex organizational processes (as in vertically integrating supply chains so that many of Tesla’s and SpaceX’s parts are made in-house), and a leader whose warped charisma can push employees through difficult deadlines. (Musk is said to have motivated, or possibly just frightened, Tesla workers during the production of the company’s Model 3 by sleeping nights on the factory floor.)

To whom could you even compare this Musk? He makes internet moguls such as Mark Zuckerberg and the Google guys look like dilettantes and their products like glorified spyware. He has been called an heir to Steve Jobs, but while Jobs might have talked about putting a “dent in the universe,” Musk is actually operating at the level of interplanetary ambition. Attempting to buy Twitter as a gag and then getting pantsed in front of the entire contract-abiding world may not engender much faith in his farthest-fetched plans to spread humanity across the cosmos. But while everybody’s laughing, his car and rocket companies are on track to keep thriving into 2023 and beyond.

Tesla is the most valuable automaker in the world even though it sells only a fraction as many cars as most of its rivals. In the second quarter of 2022, it doubled profits over the same period in 2021, which is remarkable in itself but more so given COVID-related factory shutdowns and Musk’s copious personal distractions. Coming next year (maybe) is Tesla’s second-generation Roadster, and if it ships as Musk has promised, it will be among the fastest electric cars ever made, with a top speed of over 250 mph, and the fastest-accelerating cars of any kind, able to do zero to 60 in just 1.9 seconds. SpaceX’s prospects may be even greater. The company has reduced the cost to send cargo into orbit by a factor of 20. One of its rockets, Starship, the tallest and most powerful ever built, is theoretically capable of hauling more than 100 metric tons. If Musk’s engineers can figure out how to get the prototypes to stop exploding on takeoff and landing, the Starship may someday be able to transport 100 people to the moon or Mars, then, because it’s fully reusable, flip over and blast off to Earth again. Musk has said the Starship could eventually fly for as little as $2 million per launch, which would make its cost per kilogram of payload something on the order of overnighting an envelope from Manhattan to Brooklyn.

Or maybe none of that will happen, because Musk can be an appallingly bad estimator. As his biographer Ashlee Vance has noted, engineers at one of Musk’s early start-ups learned that if he anticipated a coding task would take an hour, it would usually take two or three days, and if he thought it would take a day, it might take a couple of weeks. He has bumped the ETA for SpaceX’s first manned rocket to Mars from 2026 to 2029. He predicted that Neuralink would test its brain interface in humans by 2020; now he says by the end of 2022. In May, he said that Tesla’s self-driving Autopilot feature would eliminate the need for human drivers by next year, which is similar to claims he has made every year since at least 2014.

Still, Musk has delivered on enough laughably impossible goals that those who doubt him do so at their own risk. He seems pathologically bent on silencing critics — either by succeeding or making them sign NDAs — and he might have been designed in a lab to carry long-term grudges as motivation. He says he was bullied as a kid in Pretoria, South Africa, and once got a nose job to reopen his airways after he was beaten up and thrown down a flight of stairs. He’s estranged from his father, a person he has called “a terrible human being.” He was ousted as CEO at his first two companies — Zip2, a maker of city-guide software for newspapers that sold to Compaq for some $300 million in 1999, and X.com, which became PayPal and was sold to eBay for $1.5 billion in 2002 — so he put his own money into Tesla and SpaceX, making him harder to get rid of. Tesla’s entire 2018–21 stock run might in part have been his revenge on the short sellers that once targeted the company, including Bill Gates, who Musk alleges still hasn’t closed a multibillion-dollar short position. And to Musk’s credit, his original visions for Zip2 and PayPal, both overruled at the time, were at least partially vindicated later. He’d wanted to turn Zip2 into a consumer hub for maps and local-business reviews years before the launch of Yelp and Google Maps. And he reportedly thought PayPal should have held out for a better acquisition offer; it’s currently worth around $100 billion.

The question is whether Musk’s attempted jilting of Twitter is just one more sideshow on a general path to business glory or evidence that he’s immolating like one of those Starship prototypes. So far, his 2022 has included multiple accusations of racial discrimination from employees; a resurfaced sexual-harassment allegation from a SpaceX flight attendant; the recall of nearly 600,000 Tesla vehicles; animal-cruelty complaints against Neuralink; the discovery of three publicly unacknowledged children; and a Wall Street Journal claim that he had an affair with Sergey Brin’s estranged wife, Nicole Shanahan, that led to the Google co-founder filing for divorce. (Tesla denies the racial discrimination, Neuralink disputes the animal cruelty, and as for the affair: A lawyer for Shanahan denies it, as does Musk. “Haven’t even had sex in ages [sigh],” he posted.) None of these scandals hung around for long enough to inflict much damage in part because he tweeted right through them, creating an endless diversion.

Lately, there seems to be something purposeful about how Musk tweets the news, muscling his way into trending topics like a one-man bot farm. A tag cloud for one of his slower weeks may include climate, COVID, free speech, the 2024 election, abortion, gun control, the Russia-Ukraine war, UFOs, crypto, Elden Ring, the Johnny Depp–Amber Heard trial, and more. He has spread himself through every cultural jurisdiction so that he’s always the top story no matter which news bubble you’re in. Some billionaires own magazines and newspapers, but Musk may have built something bigger, a decentralized media empire that amplifies his every utterance into a blizzard of commentary and clickbait so that all praise, honest criticism, and exasperated overreach cancel one another out and he can wear our exhaustion like armor.

Once, during the post-dot-com innovation drought that spawned it, Twitter was the soft and ridiculous antithesis of everything that Musk, a maker of hard and serious tech, stood for. “We wanted flying cars,” went the motto of his PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel’s VC firm. “Instead we got 140 characters.” Now it’s existentially important to everything Musk does — and thanks to him, its own future has never been bleaker.

Musk’s Twitter imbroglio recalls one of his earliest vanity purchases. When Zip2 was acquired, he celebrated his first major payday by dropping $1 million on a McLaren F1, then the world’s fastest car. One afternoon, he was driving in Silicon Valley with Thiel, who asked, “So what can this do?” “Watch this,” said Musk as he stomped on the accelerator. The car hit an embankment, jumped three feet in the air, spun around, and touched down, its body and suspension totaled. “You know, I had read all these stories about people who made money and bought sports cars and crashed them,” Musk reportedly told Thiel. “But I knew it would never happen to me, so I didn’t get any insurance.” And then he climbed out of the wreck without a scratch on him.