It was the first night in November, and News Corp.’s fedora-wearing CEO Robert Thomson was partying with Kylie Jenner at the Museum of Modern Art. The two influencers were there for WSJ. magazine’s 13th annual Innovator Awards, one of those glitzy, publicist-and-luxury-brand-driven red-carpet affairs that media companies throw in order to gull advertisers and generally make everybody involved feel drunk on their own VIP-ness. This year’s ceremony was also something of a coming out for Sarah Ball, the recently installed top editor of WSJ. mag. At the dinner, she sat next to Julia Louis-Dreyfus and across from Jenner and her boyfriend, Timothée Chalamet.

Ball, 37, was promoted to the job in June, after her predecessor, Kristina O’Neill, was abruptly pushed out by Emma Tucker, The Wall Street Journal’s editor-in-chief. Tucker had arrived early this year from the Sunday Times of London, which is also owned by Rupert Murdoch. Ever since, she has been ridding the Journal of its entrenched ruling class in a series of moves designed to liven up its stodgy pages (she also got rid of things like calling people “Mr.”), but also to consolidate her power and to save money. After ousting O’Neill, Tucker took out Neal Lipschutz and Jason Anders, both éminence grise deputy editors of the news pages. More recently, she whacked Matthew Rose, the powerful page-one editor, and Paul Beckett, the Washington bureau chief. The heads keep rolling, and panic has trickled down to the rank and file. Reporters say they can’t help but detect a note of dread each time they speak to their editors. Nobody knows who might get Tucked next.

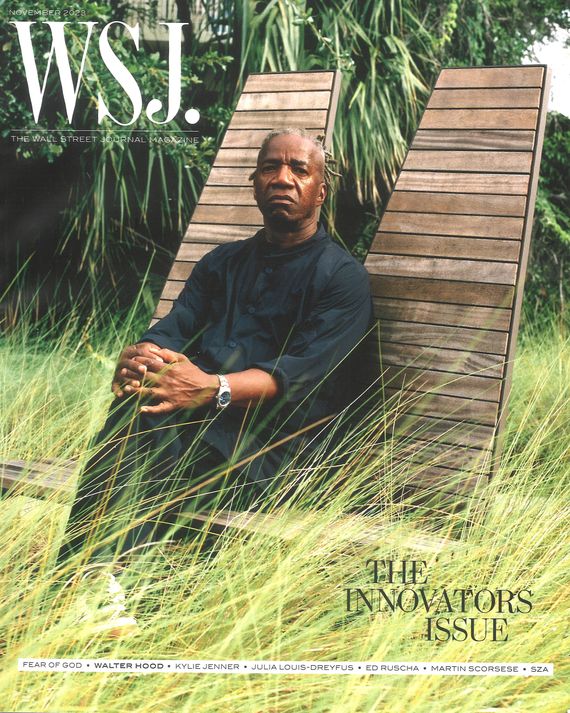

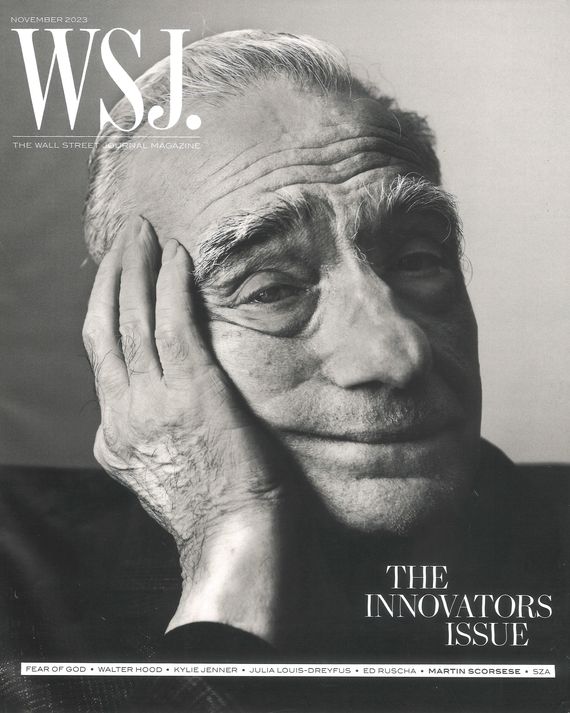

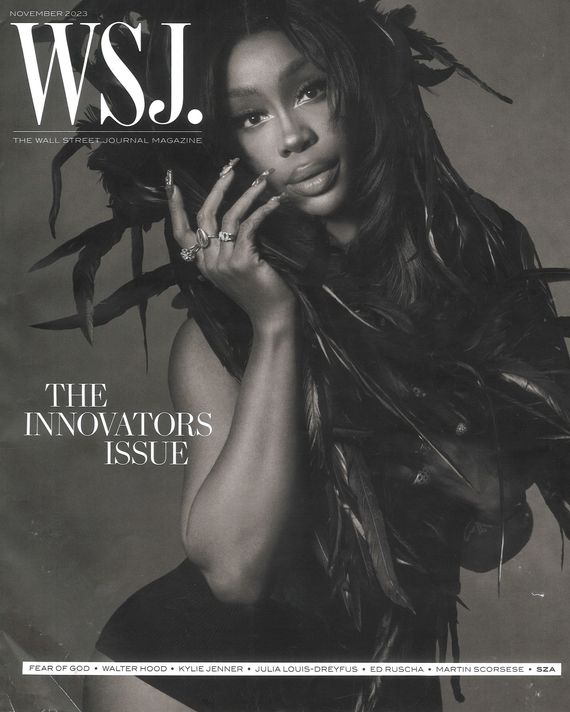

Tucker didn’t make it to the MoMA party, since she was feeling a bit under the weather that night, but Thomson and the Journal’s publisher, Almar Latour, were there, exalting in the event — it’s sort of the Journal’s version of the Time 100 — that O’Neill had built into a franchise. It gave the serious investor’s newspaper with the sometimes kooky right-wing opinion pages a reason to throw a party fit for Hollywood and fashion-industry types. Two of the seven “Innovators” in the room that night (Ed Ruscha and Jerry Lorenzo) had been wrangled by O’Neill. For many of the party guests, this was the first they were hearing of Sarah Ball. “I don’t know very much about her,” Marc Jacobs told me when I asked what he thought of her, “so I feel a little bit like I’d just be making up a lot of bullshit.” Linda Evangelista stood beside Karen Elson and said she, too, had just met Ball. “I’ll get to know her a little more this evening.”

How Ball got to be the belle of this ball is the subject of some side-eye in fashion circles and at the paper. When I called around to Journal staffers past and present, more than one person archly invoked Eve Harrington — which would make Ball’s former boss, O’Neill, whom she has now replaced, Margo Channing.

O’Neill had run WSJ. mag for the last decade, along with her creative-director husband, a Scandi dandy named Magnus Berger. Kristina and Magnus, as they’re known, became a fashion power couple, sitting front row at the runway shows and often populating the pages of their magazine with their fabulous, Barry Diller’s–yacht–adjacent friend group: Derek Blasberg, Karlie Kloss, Dasha Zhukova, and Lauren Santo Domingo. WSJ. became well respected in the fashion world and used big-name photographers like Mario Sorrenti and Peter Lindbergh. O’Neill’s WSJ. felt like a five-star resort: sleek, elitist, and grit free, all designed to be like cashmere crack to luxury advertisers.

It had been Thomson’s idea to launch it, back in 2008, to compete with T, the New York Times’ glossy, which first published in 2004. Beyond looking pretty, these ad-fattened mags, which come rolled up inside the weekend print editions of the newspapers various times a year, actually serve a higher purpose, since the money they make shilling for watches, jewelry, and face creams fund the journalism of the newsroom. As former Times editor Bill Keller once said, “If luxury porn is what saves the Baghdad bureau, so be it.” WSJ. made gobs of money and O’Neill was rewarded, becoming, per multiple sources, one of the highest-paid people in the newsroom; she apparently had a huge clothing and travel budget, like some kind of old-school Condé Nast editor. (O’Neill declined to speak with me for this column.)

In 2018, as luxury advertisers continued their shift away from print, O’Neill hired Ball from GQ to build out WSJ.’s web presence. Ball hired a small team, and in 2022, she was given a budget to start her own, digital-first “Style News” desk to complement the print mag. Soon, some on staff felt there was a quiet power struggle at play. Ball’s Style team sat with other newsroom sections on the fifth floor, while O’Neill’s magazine staff sat downstairs on four. (The brass sits up on six). When the pandemic hit, Ball went to London to work remotely, and she was still there at the top of this year when it was announced that Tucker had gotten the Journal gig, and the two met. She clearly made a good impression on her future boss.

Tucker, used to running smaller and scrappier newsrooms, was never going to keep O’Neill and Berger around. Tucker told O’Neill she was being cut the very first time the two met in person. The day the note to the newsroom went out, April 27, Tucker called Ball to tell her the job was now open, encouraging her to apply.

O’Neill stayed on a little while longer, and Berger left, too. The magazine’s photo director, who had worked there for over ten years, was laid off while she was on a train on her way into the office one day. Her email shut off before she could even get to midtown. The fourth floor was appalled. Ball’s promotion was announced June 9.

The morning after the Innovators Awards, I got Tucker on the phone to explain why she switched out O’Neill for her underling. “I was a new editor, and I wanted to take the magazine in a new direction, which I think is reasonable,” said Tucker. “The thing is, Sarah was running the ‘Style’ section with great sort of verve, and I think, as with all parts of the newsroom as well, I wanted to sort of make what we were doing in ‘Style’ more integrated with the magazine. In other words, I wanted to create one team that produces all our ‘Style’ and lifestyle content.” This was very much the Emma Tucker playbook when she ran the Sunday Times; she wiped out the old guard and promoted a number of young deputies, who then became loyal to her.

Which means it’s good to be a soft-sections reporter at the new Journal. Chattier lifestyle and service articles, which talk more directly to the readers (see just this morning on the homepage: “Ridiculously Long Men’s Coats Are in Style. So I Tried a Few.” and “This Season’s ‘It’ Jewelry Is … Old Jewelry?”), are being given more prominence. (Though the Journal’s “Off Duty” section is not part of Ball’s domain.) “Style” section reporters have been pleasantly surprised to find their trend pieces splashed across the front page of the print newspaper lately. As instructed, Ball has combined the “Style” and magazine staffs and will now oversee not just a glossy mag and an awards ceremony but a 51-person department covering fashion and arts and entertainment.

“Obviously I was floored and surprised to get this job,” Ball told me the week before her public coronation at the Innovator Awards. It was a Monday afternoon and we were meeting for lunch at the Lambs Club, sitting at a table beside that Citizen Kane–style Gothic fireplace. She wore ripped black jeans, black motorcycle boots, and a striped cashmere Khaite sweater. I asked how it felt to take over from O’Neill. “I learned a lot from her, and it’s a big act to follow,” she said, picking at a plate of chicken paillard. “I feel like she really left it in this place of strength. That’s why I’m not sitting here telling you that we’re redesigning and imploding and throwing out everything that she and Magnus built, because we just don’t have to.”

Ball, whose father was secretary of the Navy under Ronald Reagan, grew up in Alexandria, Virginia. By the time she got her start at Condé Nast, the glory days of print were over and the mad scramble to build out the websites had begun. She was a web editor at Graydon Carter’s Vanity Fair starting in 2010, then jumped to GQ under Jim Nelson, eventually becoming his editorial director (there was also a brief stint at Tatler in London). “I started in the Frank Gehry cafeteria days,” at the old Condé HQ in Times Square, she recalled, “where you really would see, like, Remnick taking Lena Dunham to lunch, and Si holding court. You really felt like, I am working for a very fizzy, dynamic cultural property.” But in 2014, the company moved to 1 World Trade Center, and it has been steadily downsizing ever since. “It’s so hard to even imagine what it must be like there in our modern office climate,” Ball said. (There were a bunch of layoffs there this week.)

Ball’s old boss at GQ, Nelson, told me, “I think her hiring is a sign that the new regime is serious about shaking things up, because, look — I don’t read The Wall Street Journal ’cause I don’t know what dividends are — but I would look at the weekend editions, and the magazine, and I always thought they were breezier, more inviting, and I thought the technology coverage and stuff was good, but it didn’t always have a ton of personality. And that might be her greatest challenge, injecting personality into the magazine.” He described Ball as “an incredibly good writer” and “fluid thinker” who always has “a smart eye on where the culture is going.” He supposes Ball will “bring in smart writers, I hope she’s able to do that,” adding that “wit is an underrated attribute in a magazine; you want your magazine to be the life of the party.”

O’Neill hired name-brand freelance writers and ran the magazine very separate from the rest of the Journal. Ball said she will get the paper’s reporters writing scoopy profiles off their beats for the mag. But if she starts getting too hard-hitting, won’t she spook the advertisers? “I think there is room for more substantive journalism, feature journalism in the magazine,” she said. “I think that’s something not only I believe but Emma really believes. I do have complete confidence that you can do that without alienating advertisers.” Two Journal reporters in particular she said she wants to tap for news-making magazine assignments are Erich Schwartzel, who covers Hollywood, and Kelly Crow, who reports on the art world.

Meanwhile, having staffers write for the magazine will save money since, unlike at the Times, reporters in other sections of the Journal are not paid extra if they write for it. So maybe this is really just some budget jiujitsu. “Oh my God,” Ball said, a bit nervously. “No, 100 percent wrong. If anything, we have more money to spend on beautiful locations and fashion shoots.”

O’Neill and her team had strong relationships with advertisers, nurtured over a decade of cocktail parties, fashion credits, product spotlights, and expense-account lunches. Ball will need to get up to speed. “In some cases, I have them from my Condé days,” she said, “and in some cases, Emma has them, which is also something that’s different for us. I’m developing these relationships now.” The first thing she did after she was appointed was fly to Milan and Paris to glad-hand the advertisers. “I had 24 meetings in three days,” she said.

She went to the runway shows, too. O’Neill’s WSJ. was supremely fashion-focused — she had come from Harper’s Bazaar — but that’s not Ball’s métier, at least not yet. “I would say I am embracing it,” she said. “I’m going to do it in a different way. I think I’m not going to do the exact same schedule, but I am going to be at multiple fashion shows a year.” Talking to people around town, some fashion folk were fretful that after years of mutual back-scratching with O’Neill, they had to start all over, or that working with Ball would be seen as disloyal to O’Neill. Others were just bitter that Ball — a comparative nobody — got this plum job, one of the last great editor gigs in magazineland. So, were the fashion people nice to her at the shows? “They were,” she said. They seem kind of scary. “They do seem scary,” she allowed. “I think I have been building it up in my mind. Then I just thought, I am who I am,” she said with a shrug and smile. The creative-director job at the magazine has not been filled. But it won’t be Ball’s husband, who covers high finance for Bloomberg.

As I told Tucker, many other people across her newsroom are starting to feel freaked out, not just by the volume of the layoffs but by the way in which they’ve been conducted. Last month, after she pulled Beckett, the Washington bureau chief who is Scottish — reporters have been darkly joking that “he’s from the empire, but not the right part” — the bureau was thrown into chaos just as the news cycle in Washington hit warp speed, what with the Speaker catastrophe, a new war, and the start of the presidential campaign. People down there are wondering why Tucker would do that if she didn’t have a replacement lined up (there still hasn’t been one named; Beckett remains at the Journal in a new role focused on securing the release of reporter Evan Gershkovich, who was detained by the Russians). “There will be a replacement!” Tucker protested. “We just, you know, we have to do a process, it’s not like I’m not going to have a D.C. bureau chief.” She continued, “If I just came in and did nothing, I wouldn’t be doing my job. So, you know, I set out very clearly where I want the Journal to head, but in order to get there, I’m going to have to make changes along the way. And what’s really satisfying for me is that the people who get it are really onboard with it, and there’s a lot of energy and excitement about where we’re headed, and the realization that we can’t just carry on doing things the way they’ve always been done.”

Lately, a rumor has begun spreading through the newsroom that Tucker came to New York with ulterior motives. Staffers are starting to suspect her entire purpose is to reduce operating costs as much as she can to prepare the Journal for a sale once Lachlan Murdoch truly takes over from his father, since the son has never seemed all that fond of the pesky newspaper business — after which point, Tucker could return to London. “You can’t do this in a company full of people who cover business news and not have people wonder if that’s what’s up,” says one reporter there. “It feels very much like we’re being cleaned up for a sale.”

But Tucker scoffs at this. “Honestly, having worked for different News Corp. papers, that is a kind of perennial, that one is always there; at any tough point at the time I’ve worked for News Corp., there’s always been this thing of, Oh, they’re getting it ready for a sale!” She laughed and added, “If that’s the case, I don’t know about it.”