Three years ago, nobody knew who you were. And now you’re sitting on the cover of magazines. And you’re a gazillionaire. And your business is, like, one of the fastest-growing businesses in the history of the planet.”

Sam Bankman-Fried giggled and nodded nervously, shaking his messy crown of curly hair, as the writer Michael Lewis lavished him with praise. They were onstage at a resort in the Bahamas for a conference put on by the 30-year-old billionaire to celebrate the success of his crypto exchange, FTX. It was April 2022, and pretty much everyone who mattered in the world of virtual currencies had flown in for the occasion — plus Bill Clinton, Katy Perry, and Tom Brady for good measure.

Bankman-Fried was dressed slovenly as usual, in gray shorts and a gray FTX T-shirt. Lewis looked like a prep-school headmaster, wearing a blue blazer with peak lapels and a white button-down with blue accents, his floppy hair parted perfectly to the side. The way he was talking about Bankman-Fried, he sounded as if he were presenting a prize to his star pupil. “You’re breaking land-speed records,” Lewis said. “And I don’t think people are really noticing what’s happened, just how dramatic the revolution has become.”

I’d heard that Bankman-Fried was going to be the subject of Lewis’s next book. But the author’s questions were so fawning they seemed inappropriate for a journalist. Listening from the packed auditorium, I started to question whether Lewis was really writing a work of nonfiction or if FTX had paid him to appear. (Lewis later told me that he was there as a reporter and that he was not compensated.)

I’d come to the Bahamas because I was about a year into an investigation of the crypto world. I wanted to understand why the prices of bitcoin and hundreds of lesser coins — with ridiculous names like dogecoin, solana, polkadot, and Smooth Love Potion — were going up and up. Crypto boosters claimed they were in the vanguard of a revolution that would democratize finance and create generational wealth for those who believed. The roar of the rising prices drowned out the skeptics. Incomprehensible jargon became inescapable. Blockchain. DeFi. Web3. The metaverse. What these terms meant was beside the point. Newspapers, TV, and social media bombarded readers with stories of regular people who invested and got rich virtually overnight.

Crypto seemed like a giant slot machine that had been rigged to pay out almost every time. Hundreds of millions of people around the world gave in to the temptation to pull the lever. Everybody knew somebody who’d hit it big. And the more people who bought in, the higher prices rose. By the time of the conference in the Bahamas, the total market value of all of crypto was $2 trillion.

From the beginning, I had thought that crypto was pretty dumb. And it turned out to be even dumber than I imagined. There was no mass movement to actually use crypto in the real world. The crypto apps hyped as the future of finance and art barely worked. As I crisscrossed the globe, from El Salvador to Switzerland to the Philippines, all I saw were scams, fraud, and half-baked schemes. By the end, I’d find myself in Cambodia, investigating how crypto fueled a vast human-trafficking scheme run by Chinese gangsters.

I’d grown up reading Lewis’s books, including Liar’s Poker and The Big Short, and when he and Bankman-Fried first came onstage, I was excited to hear insights from the guy who taught me how Wall Street blew up the world economy with collateralized debt obligations. Instead, Lewis said he knew next to nothing about cryptocurrency. But he seemed quite confident that it was great. He went on to opine that, contrary to popular opinion, crypto was not well suited for crime. Lewis posited that U.S. regulators were hostile to the industry because they’d been brainwashed or bought off by established Wall Street banks. I wondered if he somehow hadn’t heard about the countless crypto scams, but the thought seemed preposterous.

“You look at the existing financial system, then you look at what’s been built outside the existing financial system by crypto, and the crypto version is better,” Lewis said.

Bankman-Fried’s other turns onstage at the conference were similarly mindless. He stumbled through an interview with the former British prime minister Tony Blair and Clinton, who at one point extended a fatherly hand of support. He exchanged banalities about charity with Gisele Bündchen, with whom he’d posed for an FTX ad campaign that ran in Vogue and GQ, and platitudes about leadership with her husband, Tom Brady.

“Does it ever get boring to win so much?” a moderator asked.

“I get a little desensitized,” Bankman-Fried said.

“I never get tired of winning,” Brady said.

It was depressing to see that many people whom I had admired had been co-opted by Bankman-Fried to promote crypto gambling. I’d later learn Brady and Bündchen were paid about $50 million in stock for their endorsements. Clinton was reportedly paid at least $250,000 to appear at the conference.

The crowd there lacked the quasi-religious fervor I’d seen at more plebeian crypto gatherings. Instead, the attendees fell into three groups. There were the venture capitalists, who’d gotten in early, watched the tokens they bought climb to ludicrous heights, and now believed they could predict the future. There were the founders of crypto start-ups, who’d raised so many millions of dollars that they seemed to believe their own far-fetched pitches about creating the next generation of finance. Then there were the programmers, who were so caught up with their clever ideas about new things to do inside the crypto world that they never paused to think about whether the technology did anything useful.

At a party for a project called Degenerate Trash Pandas, I asked one coder if crypto would ever be helpful for regular people. “Why is it that you think that is important?” he said to me, in total sincerity. “I really would like to know.”

In the press room, I saw Kevin O’Leary — the Shark Tank judge who goes by “Mr. Wonderful” — polishing his already shiny dome with an electric razor as he prepared to go on TV. (He was paid $15 million to endorse FTX.) And I spotted a man from New York I’d investigated years earlier. He sometimes went by the alias “Jim Stark,” though his real name was Andrew Masanto, and he’d been accused in three lawsuits filed by angry consumers of involvement with a “plant stem cell” miracle hair-loss cure. (He has denied the connection.) After I awkwardly reintroduced myself, he told me he was building a “Web3 social platform” and that he had helped create a popular cryptocurrency. I looked up its market value and saw it was almost $4 billion.

“There’s a lot of legitimacy behind the technology,” he said.

Before I got to the Bahamas, I’d thought the conference’s attendees might be chastened by the recent failure of a high-profile crypto app called Axie Infinity. It was a Pokémon-ish mobile game in which players bought creatures with virtual currency and battled to win tokens called Smooth Love Potions. Amazingly, crypto boosters had promoted this as a potential replacement for actual jobs. Hundreds of thousands of people in poor countries had gotten sucked in, even taking out loans to play, before the unsustainable bubble had unsurprisingly collapsed.

Making matters worse, in March 2022, a month before the conference, North Korean hackers broke into a sort of crypto exchange affiliated with Axie Infinity and made off with $600 million worth of crypto. The heist helped Kim Jong Un pay for test launches of ballistic missiles, according to U.S. officials. Instead of providing a new way for poor people to earn cash, Axie Infinity funneled their savings to a dictator’s weapons program.

But instead of any reflection on what happened, all I heard was hype. Through FTX’s press representatives, I arranged a string of interviews with attendees. One was with John Wu, the president of Ava Labs, which ran a popular blockchain called Avalanche and had recently been valued at $5 billion. If anyone at the conference was going to be sober-minded, I imagined it would be him. Wu was 51, and his résumé included Cornell University, Harvard Business School, and a stint at the giant hedge fund Tiger Global.

But when we sat down, Wu and a colleague bragged to me about a Zelda-like play-to-earn game on their blockchain that had attracted 40,000 users in less than a month. They said the game was teaching people about DeFi — decentralized finance, a way of trading without a central counterparty — and letting them earn high returns. It sounded a lot like Axie Infinity. I couldn’t believe they were pitching it with a straight face after Axie’s collapse. “You can get 10 percent in DeFi,” Wu said. “You can be a true freelancer. There are literally people who quit their jobs. It’s not magic. If you know what you’re doing here, you’re going to change your life.”

Michael Wagner, the founder of a space-themed crypto game called Star Atlas, even cited Axie Infinity as a proof of concept. Instead of colorful blobs and Smooth Love Potions, Star Atlas players had to buy spaceship NFTs to earn atlas tokens, and he told me he’d already sold nearly $200 million worth of them. But when I asked if I could try out the game, he said it didn’t exist yet. Even though he’d already sold the spaceships, he said it would be at least five years before the game was ready. “It’s very early stage,” he said. “We believe the game could bring in billions of users.”

Another crypto executive showed me a digital image of a sneaker that he’d bought for $8 and that he said was now worth more than $1 million. He told me that recently, all owners of these imaginary sneakers had been issued an image of a box, which was itself worth $30,000. When he opened the box, he found another picture of sneakers and another box, each of them valuable in their own right. “It’s this never-ending Ponzi scheme,” he said happily. “That’s what I call Ponzinomics.”

The most popular “real world” use of crypto seemed to be an app called Stepn. It tracked users’ movement, paying them in “green satoshis” for walking or running. Users had to first buy virtual sneakers, which cost $500 or $1,000. This was definitely Axie all over again, but no one seemed to care. A writer who visited FTX’s offices around that time noticed employees walking around the parking lot to earn crypto in Stepn. The company that made the app was earning around $40 million a month.

“What do you say to critics who say that — and they probably say this about a lot of projects — but like … this is a Ponzi scheme,” I asked Stepn’s co-founder, Yawn Rong, over Zoom, trying to be polite.

Rong, a 37-year-old former tile wholesaler in Australia, was not offended. He acknowledged the similarities right away. “Yes, it is a Ponzi structure. But it is not a Ponzi,” he said.

Rong explained that in a true Ponzi scheme, the organizer would have to handle the “fraud money.” Instead, he gave the sneakers away and then only took a small cut of each trade. “The users are trading between each other. They are not going through me, right?” Rong said. Essentially, he was arguing that by downloading the Stepn app and walking to earn tokens, crypto bros were Ponzi-ing themselves.

It struck me that almost any of the companies I’d heard about would be good fodder for an investigative story. But the thought of methodically gathering facts to disprove their ridiculous promises was exhausting. It reminded me of a maxim called the “bullshit asymmetry principle,” coined by an Italian programmer. He was describing the challenge of debunking falsehoods in the internet age. “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it,” the programmer, Alberto Brandolini, wrote in 2013.

A day before the start of the Bahamas conference, Bankman-Fried had all but admitted that much of his industry was built on bullshit. During an interview on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast, the columnist Matt Levine asked a straightforward question about a practice called yield farming. As Bankman-Fried attempted to explain how it worked, he more or less laid out the how-to of running a crypto pyramid scheme.

“You start with a company that builds a box,” Bankman-Fried said. “They probably dress it up to look like a life-changing, you know, world-altering protocol that’s gonna replace all the big banks in 38 days or whatever. Maybe for now actually ignore what it does — or pretend it does literally nothing.”

Bankman-Fried explained that it would take very little effort for this box to issue a token that would share in the profits from the box. “Of course, so far, we haven’t exactly given a compelling reason for why there ever would be any proceeds from this box, but I don’t know, you know, maybe there will be,” Bankman-Fried said.

Levine said that the box and its “Box Token” should be worth zero. Bankman-Fried didn’t disagree. But he said, “In the world that we’re in, if you do this, everyone’s gonna be like, ‘Ooh, Box Token. Maybe it’s cool.’” Curious people would start buying Box Token. And the box could start giving out free Box Token to anyone who put money inside, just as Axie had rewarded players with Smooth Love Potions. Crypto investors would see they could earn a higher yield by putting their money in the box than in a bank. Before long, Bankman-Fried said, the box would be stuffed with hundreds of millions of dollars, and the price of Box Token would be rising. “This is a pretty cool box, right? Like, this is a valuable box, as demonstrated by all the money that people have apparently decided should be in the box. And who are we to say that they’re wrong about that?” Sophisticated players would put more and more money in the box, Bankman-Fried said, “and then it goes to infinity. And then everyone makes money.”

After a moment of contemplation, Levine said, “I think of myself as, like, a fairly cynical person. And that was so much more cynical than how I would’ve described farming. You’re just like, ‘Well, I’m in the Ponzi business and it’s pretty good.’”

Bankman-Fried said that was a reasonable response. “I think there’s like a sort of depressing amount of validity …” he said, trailing off.

I was not surprised that Bankman-Fried had been so candid, but it didn’t make me feel very good. Three weeks earlier, I’d written a profile of him. I’d built the piece around the question of whether he really would give his money away — Bankman-Fried claimed he had only gotten rich to give it away but seemed to be spending more on marketing than philanthropy — and I’d been much less focused on the potentially scammy basis of his entire industry.

In the Bahamas, I was able to wrangle a quick meeting with Bankman-Fried outside the press room. “Did I go too easy on you?” I asked.

“Maybe,” he said. A few minutes later he ran off to meet Tom Brady for lunch.

The next time I saw him was in November 2022, in the lobby beneath his $30 million apartment. It was eight days after FTX declared bankruptcy with $8 billion of his customers’ money gone missing. On the way over, I had imagined Bankman-Fried’s mood would be grim. I’d even worried that he might be suicidal. But when he greeted me, shoeless, in his familiar wrinkled uniform, he seemed surprisingly upbeat.

“It’s been an interesting few weeks,” Bankman-Fried said, and together we rode the elevator up to his penthouse.

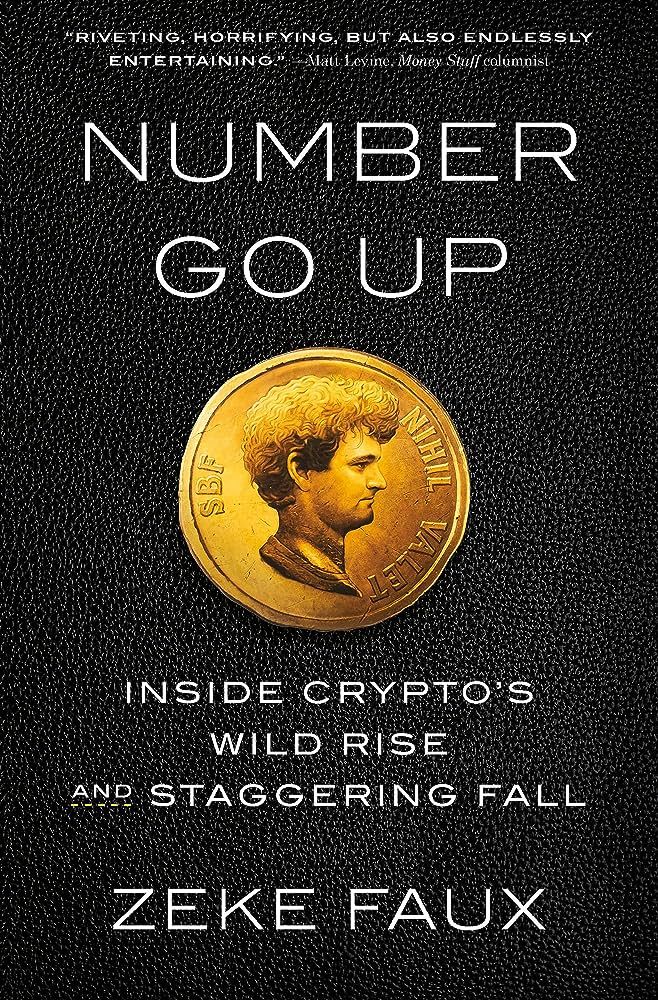

Adapted from Number Go Up: Inside Crypto’s Wild Rise and Staggering Fall, by Zeke Faux. Copyright © 2023 by Zeke Faux. Excerpted by permission of Currency, an imprint of Crown Publishing, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

More on Sam Bankman-Fried

- The Effective Altruists’ Castle Is for Sale — and Has Become a Culture-War Meme

- Sam Bankman-Fried’s Final Trip to Court

- SBF Planned to ‘Come Out As Republican’ With Tucker Carlson